Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Ann Clin Nutr Metab > Volume 14(2); 2022 > Article

- Original Article Provision of Enteral Nutrition in the Surgical Intensive Care Unit: A Multicenter Prospective Observational Study

-

Chan-Hee Park, M.D.1

, Hak-Jae Lee, M.D.2

, Hak-Jae Lee, M.D.2 , Suk-Kyung Hong, M.D., Ph.D.2

, Suk-Kyung Hong, M.D., Ph.D.2 , Yang-Hee Jun, M.D., Ph.D.2

, Yang-Hee Jun, M.D., Ph.D.2 , Jeong-Woo Lee, M.D.1

, Jeong-Woo Lee, M.D.1 , Nak-Jun Choi, M.D.3

, Nak-Jun Choi, M.D.3 , Kyu-Hyouck Kyoung, M.D., Ph.D.4

, Kyu-Hyouck Kyoung, M.D., Ph.D.4

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.15747/ACNM.2022.14.2.66

Published online: December 1, 2022

1Division of Trauma Surgery, Department of Surgery, Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center, Daegu, Korea

2Division of Acute Care Surgery, Department of Surgery, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

3Division of Acute Care Surgery, Department of Surgery, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, Korea

4Department of Trauma Surgery, Ulsan University Hospital, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Ulsan, Korea

- Corresponding author: Hak-Jae Lee E-mail lhj206@hanmail.net ORCID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7016-5076

© The Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition and The Korean Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 649 Views

- 13 Download

Abstract

-

Purpose Timely enteral nutrition (EN) is important in critically ill patients. However, use of EN with critically ill surgical patients has many limitations. This study aimed to analyze the current status of EN in surgical intensive care units (ICUs) in South Korea.

-

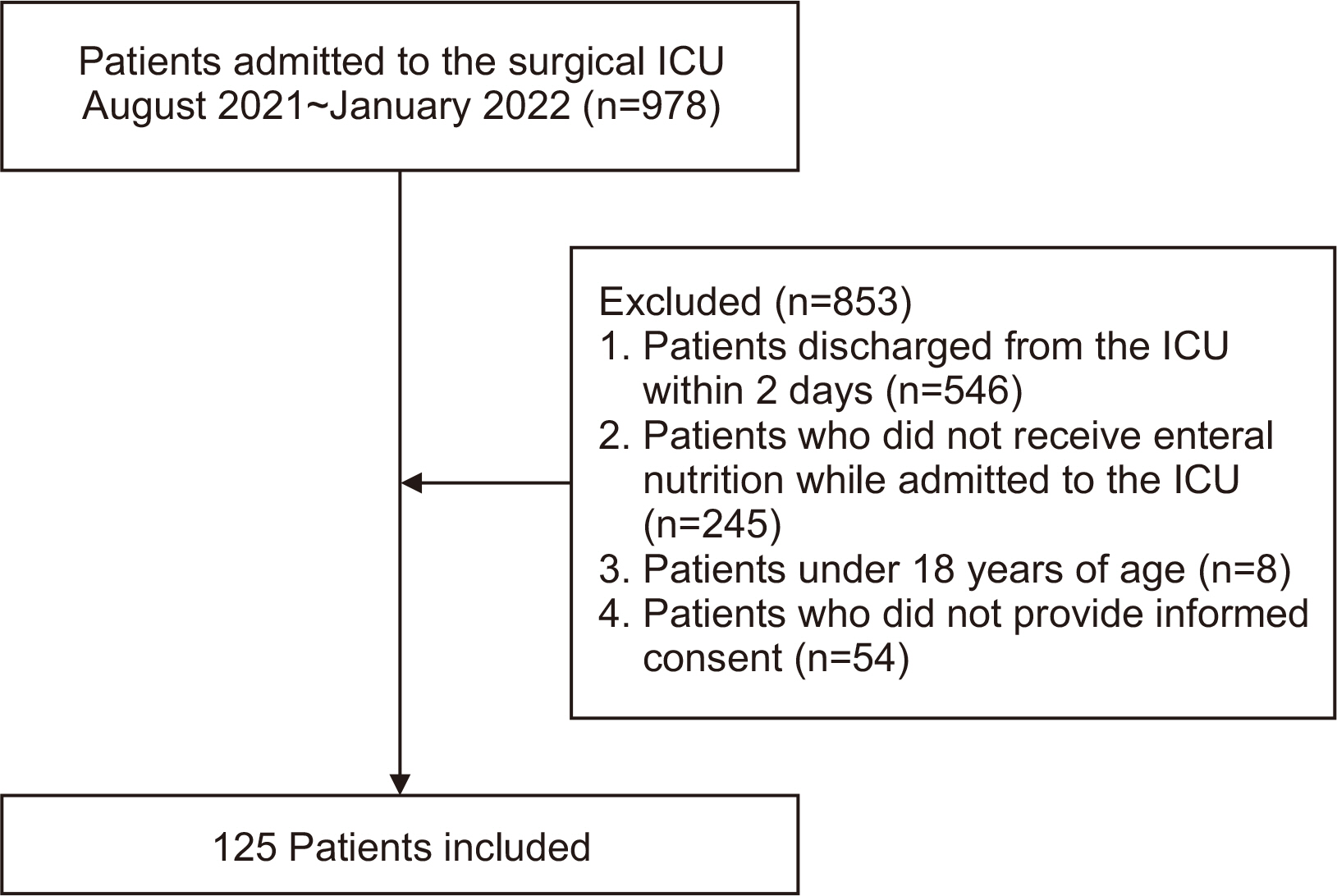

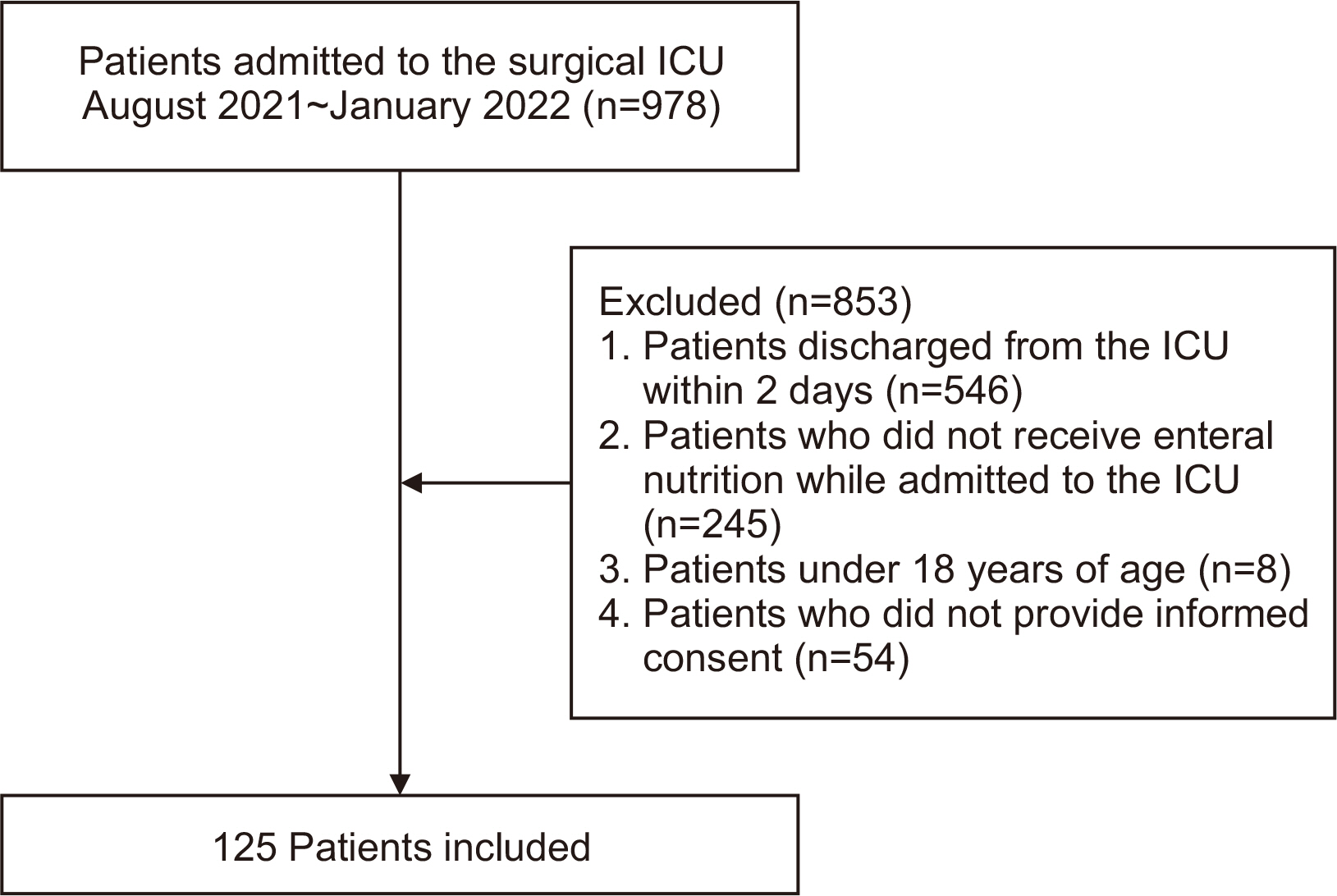

Materials and Methods A multicenter, prospective, observational study was conducted on patients who received EN in surgical ICUs at four university hospitals between August 2021 and January 2022.

-

Results This study included 125 patients. The mean time to start EN after admission to the surgical ICU was 6.2±4.6 days. EN was provided to 34 (27.2%) patients within 3 days after ICU admission. At 15.7±15.9 days, the target caloric requirement was achieved by 74 (59.2%) patients through EN alone. Furthermore, 104 (83.2%) patients received supplemental parenteral nutrition after a mean of 3.5±2.1 days. Only one of the four hospitals regularly used enteral feeding tubes and post-pyloric feeding tubes.

-

Conclusion Establishing EN guidelines for critically ill surgical patients and setting an appropriate insurance fee for EN-related devices, such as the feeding pump and enteral feeding tube, are necessary.

INTRODUCTION

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSION

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: HJL, SKH. Data Curation : HJL, YHJ, JWL, CHP, NJC, KHK. Formal analysis: HJL, YHJ. Funding acquisition: HJL. Investigation: HJL, JWL, CHP, NJC, KHK. Methodology: HJL, SKH. Project administration: HJL, JWL, CHP, NJC, KHK. Resources: HJL, YHJ. Software: HJL. Supervision: SKH, KHK. Validation: HJL, YHJ. Visualization: HJL, CHP. Writing – original draft: CHP. Writing – review & editing: HJL, CHP.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition (KSSMN).

| Characteristics | Medical problem (n=35) | Surgical problem (n=64) | Trauma (n=26) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

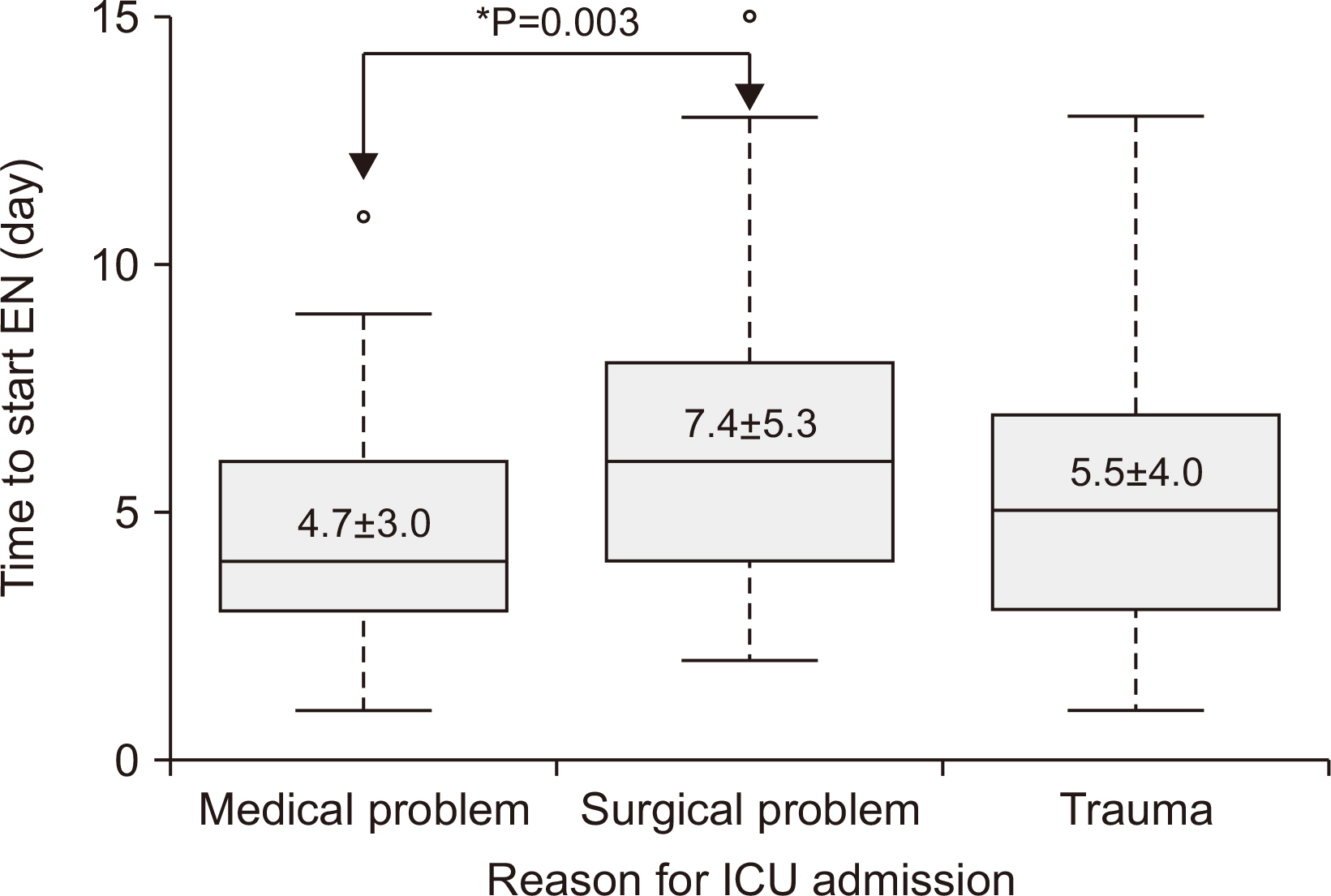

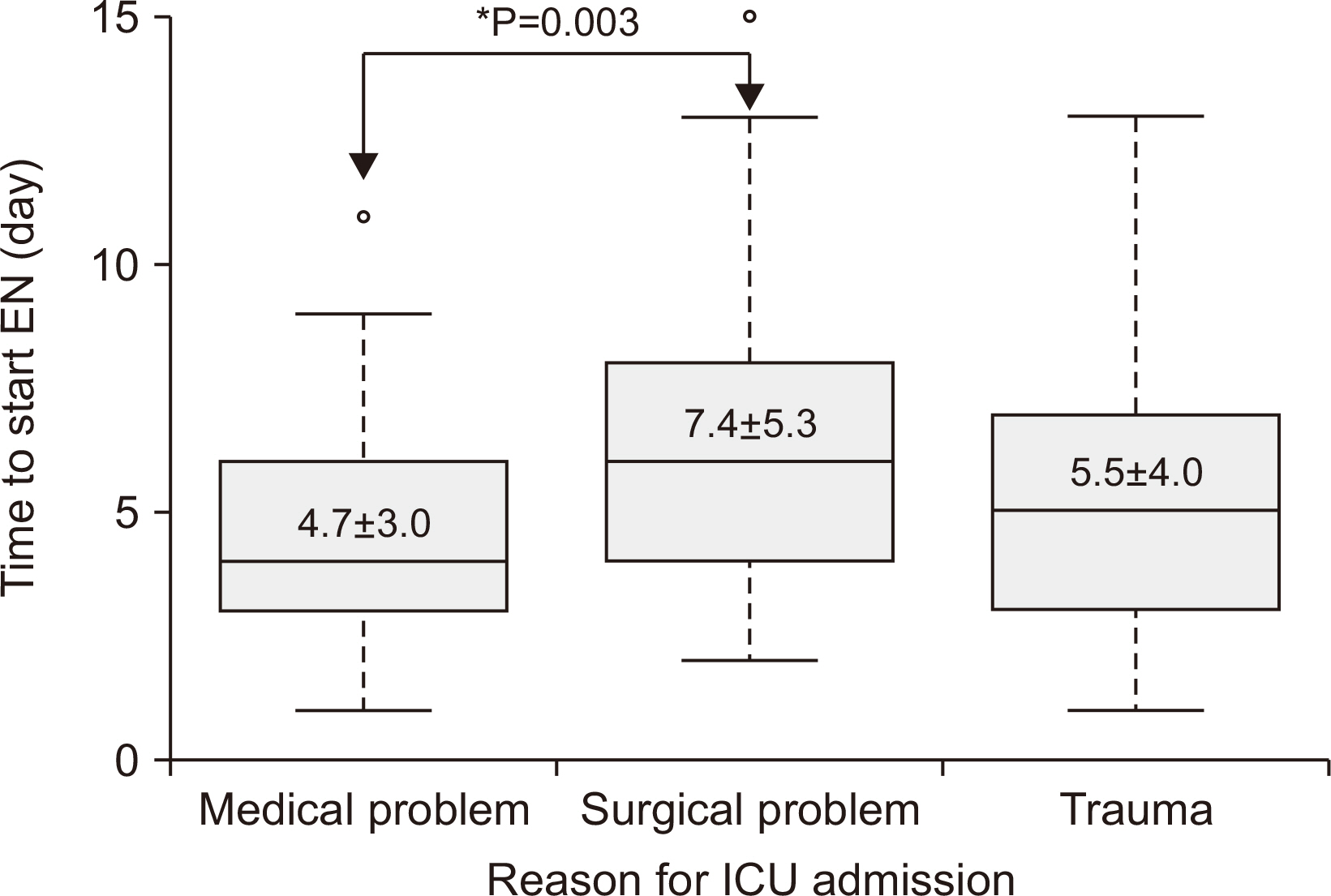

| Time to start EN after ICU admission (day) | 4.7±3.0a | 7.4±5.3a | 5.5±4.0 | 0.012* |

| Patients who received EN within 3 days | 15 (42.9)a | 8 (12.5)a | 11 (42.3) | 0.001* |

| Achievement of target caloric requirement with EN (day) | 12.4±12.6 | 20.2±19.7 | 16.6±15.8 | 0.100 |

| Use of supplemental PN | 29 (82.9) | 53 (82.8) | 22 (84.6) | 0.977 |

| Time to start supplemental PN after instillation of EN (day) | 3.1±1.8 | 3.6±1.6 | 3.8±3.4 | 0.472 |

- 1. Drover JW, Cahill NE, Kutsogiannis J, Pagliarello G, Wischmeyer P, Wang M, et al. Nutrition therapy for the critically ill surgical patient: we need to do better! JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2010;34:644-52. PubMed

- 2. Kim BC, Lee IK, Kim EY. Analysis of current status and predisposing factors for nutritional support of patients in surgical intensive care unit. Surg Metab Nutr 2016;7:32-8. Article

- 3. McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, Warren MM, Johnson DR, Braunschweig C, et al. American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2016;40:159-211; Erratum in: JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2016;40:1200. PubMed

- 4. Singer P, Blaser AR, Berger MM, Alhazzani W, Calder PC, Casaer MP, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr 2019;38:48-79. ArticlePubMed

- 5. Cerra FB, Benitez MR, Blackburn GL, Irwin RS, Jeejeebhoy K, Katz DP, et al. Applied nutrition in ICU patients. A consensus statement of the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest 1997;111:769-78. ArticlePubMed

- 6. Reintam Blaser A, Starkopf J, Alhazzani W, Berger MM, Casaer MP, Deane AM, et al. ESICM Working Group on Gastrointestinal Function. Early enteral nutrition in critically ill patients: ESICM clinical practice guidelines. Intensive Care Med 2017;43:380-98. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 7. Chang SJ, Kim H. Barriers to enteral feeding of critically ill adults in Korea. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2019;28:238-45.PubMed

- 8. Habib M, Murtaza HG, Kharadi N, Mehreen T, Ilyas A, Khan AH, et al. Interruptions to enteral nutrition in critically ill patients in the intensive care unit. Cureus 2022;14:e22821. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Hise ME, Halterman K, Gajewski BJ, Parkhurst M, Moncure M, Brown JC. 2007;Feeding practices of severely ill intensive care unit patients: an evaluation of energy sources and clinical outcomes. J Am Diet Assoc 107:458-65. ArticlePubMed

- 10. Factum CS, de Souza Moreira TH, Rocha CDN, Saldanha MF, Silva FM, Jansen AK. Calorie and protein delivery in critically ill surgical and non-surgical patients receiving enteral nutrition therapy. Rev Chil Nutr 2020;47:916-24. Article

- 11. Casaer MP, Mesotten D, Hermans G, Wouters PJ, Schetz M, Meyfroidt G, et al. Early versus late parenteral nutrition in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med 2011;365:506-17. ArticlePubMed

- 12. Gao X, Liu Y, Zhang L, Zhou D, Tian F, Gao T, et al. Effect of early vs late supplemental parenteral nutrition in patients undergoing abdominal surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2022;157:384-93. PubMedPMC

- 13. Seol EM, Kwon KS, Kim JG, Kim JT, Kim J, Moon SM, et al. Nutritional therapy related complications in hospitalized adult patients: a Korean multicenter trial. J Clin Nutr 2019;11:12-22. Article

- 14. Kim H, Stotts NA, Froelicher ES, Engler MM, Porter C. Enteral nutritional intake in adult Korean intensive care patients. Am J Crit Care 2013;22:126-35. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 15. Chinda P, Poomthong P, Toadithep P, Thanakiattiwibun C, Chaiwat O. The implementation of a nutrition protocol in a surgical intensive care unit; a randomized controlled trial at a tertiary care hospital. PLoS One 2020;15:e0231777. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 16. Park H, Lim SY, Kim S, Kim HS, Kim S, Yoon HI, et al. 2022;Effect of a nutritional support protocol on enteral nutrition and clinical outcomes of critically ill patients: a retrospective cohort study. Acute Crit Care 37:382-90. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 17. Preiser JC, Arabi YM, Berger MM, Casaer M, McClave S, Montejo-González JC, et al. A guide to enteral nutrition in intensive care units: 10 expert tips for the daily practice. Crit Care 2021;25:424.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

References

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Status of enteral nutrition in the surgical intensive care units of four participating hospitals

| Hospital | Number of surgical ICU beds | Number of EN solutions prescribed in the ICU (RTH, non-RTH) | Regular use of a feeding pump in the ICU | Average number of feeding pumps used per day | NST consult for ICU patients | EN protocol in the ICU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 14 | 16 (4, 12) | Yes | 6~10 | Yes | Yes |

| B | 16 | 17 (10, 7) | No | 2~4 | Yes | Yes |

| C | 20 | 16 (7, 9) | Yes | 3 | Yes | Yes |

| D | 14 | 18 (8, 10) | No | 2 | Yes | No |

ICU = intensive care unit; EN = enteral nutrition; RTH = ready to hang; NST = nutritional support team.

Clinical characteristics associated with EN

| Characteristics | Value (n=125) |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 65.98±16.97 |

| Sex (male) | 73 (58.4) |

| Reason for ICU admission | |

| Postoperative monitoring | 29 (23.2) |

| Sepsis | 49 (39.2) |

| Trauma | 22 (17.6) |

| Respiratory failure | 12 (9.6) |

| Other | 13 (10.4) |

| Length of ICU stay (day) | 26.2±23.9 |

| Length of hospital stay (day) | 58.65±40.6 |

| Time to EN after ICU admission (day) | 6.2±4.6 |

| Patients who received EN within 3 days | 34 (27.2) |

| Reason for not starting EN within 3 days (among 91 patients) | |

| Unstable vital sign | 40 (44.0) |

| Anastomosis leakage | 24 (26.4) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 4 (4.4) |

| Ileus | 2 (2.2) |

| Other | 21 (23.1) |

| Administration of EN solution at outset | |

| Continuous feeding | 118 (94.4) |

| Intermittent feeding | 7 (5.6) |

| Achievement of target caloric requirement by EN alone | 74 (59.2) |

| Time of achievement of target caloric requirement with EN (day) (among 74 patients) | 15.7±15.9 |

| Use of supplemental PN | 104 (83.2) |

| Time to start supplemental PN after instillation of EN (day) (among 104 patients) | 3.5±2.1 |

| Patients who underwent feeding interruption | 66 (52.8) |

| Reason for feeding interruption (among 66 patients) | |

| Excess GRV | 22 (33.3) |

| Diarrhea | 9 (13.6) |

| Aspiration | 7 (10.6) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 3 (4.5) |

| Unstable vital sign | 5 (7.6) |

| Repeat procedure or operation | 10 (15.2) |

| Other | 10 (15.2) |

| Intervention for feeding interruption (among 66 patients) | |

| Change of medication dose | 30 (45.5) |

| Treatment with Clostridium difficile | 3 (4.5) |

| Insertion of post-pyloric feeding tube | 12 (18.2) |

| No oral food intake (NPO) | 19 (28.8) |

| Other (PTGBD, colostomy) | 2 (3.0) |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

EN = enteral nutrition; ICU = intensive care unit; PN = parenteral nutrition; GRV = gastric residual volume; NPO = nil per os; PTGBD = percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage.

Comparison of EN characteristics by hospital

| Hospital | Number of enrolled patients | Time to start EN (day) | Patients who received EN within 3 days | Use of supplemental PN | Time to start supplemental PN (day) | Use of enteral feeding tube | Use of post-pyloric feeding tube | Use of gastrostomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 54 | 5.9±3.6 | 15 (27.8) | 43 (79.6) | 4.1±1.6 | 24 (44.4) | 11 (20.4) | 5 (9.3) |

| B | 25 | 4.7±3.7 | 12 (48.0) | 19 (76.0) | 3.5±3.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 5 | 4.4±1.9 | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | 7.0±4.6 | 0 | 1 (20.0) | 0 |

| D | 41 | 7.7±6.1 | 5 (12.2) | 39 (95.1) | 2.6±0.8 | 2 (4.9) | 0 | 6 (14.6) |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

EN = enteral nutrition; PN = parenteral nutrition.

EN and PN statistics according to reason for ICU admission

| Characteristics | Medical problem (n=35) | Surgical problem (n=64) | Trauma (n=26) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to start EN after ICU admission (day) | 4.7±3.0 |

7.4±5.3 |

5.5±4.0 | 0.012 |

| Patients who received EN within 3 days | 15 (42.9) |

8 (12.5) |

11 (42.3) | 0.001 |

| Achievement of target caloric requirement with EN (day) | 12.4±12.6 | 20.2±19.7 | 16.6±15.8 | 0.100 |

| Use of supplemental PN | 29 (82.9) | 53 (82.8) | 22 (84.6) | 0.977 |

| Time to start supplemental PN after instillation of EN (day) | 3.1±1.8 | 3.6±1.6 | 3.8±3.4 | 0.472 |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

EN = enteral nutrition; PN = parenteral nutrition; ICU = intensive care unit.

aPost-hoc analysis was performed by Bonferroni method. *P-value <0.05.

ICU = intensive care unit; EN = enteral nutrition; RTH = ready to hang; NST = nutritional support team.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%). EN = enteral nutrition; ICU = intensive care unit; PN = parenteral nutrition; GRV = gastric residual volume; NPO = nil per os; PTGBD = percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%). EN = enteral nutrition; PN = parenteral nutrition.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%). EN = enteral nutrition; PN = parenteral nutrition; ICU = intensive care unit. aPost-hoc analysis was performed by Bonferroni method. *P-value <0.05.

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite