Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Ann Clin Nutr Metab > Volume 14(2); 2022 > Article

- Case Report Development of Wernicke’s Encephalopathy during Total Parenteral Nutrition Therapy without Additional Multivitamin Supplementation in a Patient with Intestinal Obstruction: A Case Report

-

Cheong Ah Oh, M.D.

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.15747/ACNM.2022.14.2.93

Published online: December 1, 2022

Department of Hospital Medicine, Inha University Hospital, Incheon, Korea

- Corresponding author: Cheong Ah Oh E-mail caoh@inhauh.com ORCID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1115-5150

• Received: October 17, 2022 • Revised: November 14, 2022 • Accepted: November 16, 2022

© The Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition and The Korean Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 773 Views

- 13 Download

Abstract

- Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE) is a serious neurological disorder that can be fatal if not properly treated. In this current paper, I present the case of a 51-year-old male with a perivesical fistula between a presacral abscess and the rectus abdominis muscle. He received total parenteral nutrition therapy during a fasting period because of small bowel obstruction and later developed WE. The patient’s WE-related symptoms improved following rapid treatment with high doses of thiamine.

INTRODUCTION

Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE) is an acute and life-threatening neuropsychiatric disorder caused by thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency, which is characterized by oculomotor dysfunction, mental state changes, and ataxia [1-3]. WE is a medical emergency; if it not treated immediately and properly, irreversible brain damage (such as Korsakoff psychosis) and even death may occur [4,5]. The mortality rate associated with WE is 17%, and its symptoms are completely reversible with early diagnosis and treatment [6].

WE is frequently reported in patients with hyperemesis gravidarum and dialysis-related loss of thiamine, in those who undergo chemotherapy or bariatric surgery and in people with long-term alcohol abuse [1,7-10]. However, long-term total parenteral nutrition (TPN) therapy with insufficient multivitamin support can also cause WE iatrogenically [1,3,7-10]. Parenteral nutrition (PN) is often given to increase or ensure nutrient intake in malnourished patients, but it is a complex therapy that requires a robust system to ensure its safety and efficacy [11]. While standardized commercial PN formulations have substantially improved safety and quality along with the advantage of cost savings and convenience, they may still require supplementation with vitamins, minerals, and trace elements to meet the micro-nutrient requirement in the majority of patients [6,10].

I report the case of a 51-year-old male on long-term TPN because of small bowel obstruction (SBO) who developed WE due to a lack of vitamin supplementation during the nulla per os (NPO) period. This case highlights the importance of appropriate vitamin supplementation for patients on long-term TPN, and rapid treatment with high doses of thiamine, when there is any clinical suspicion of WE in those patients [12]. This case study was conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inha University Hospital (no. 2022-06-009).

CASE REPORT

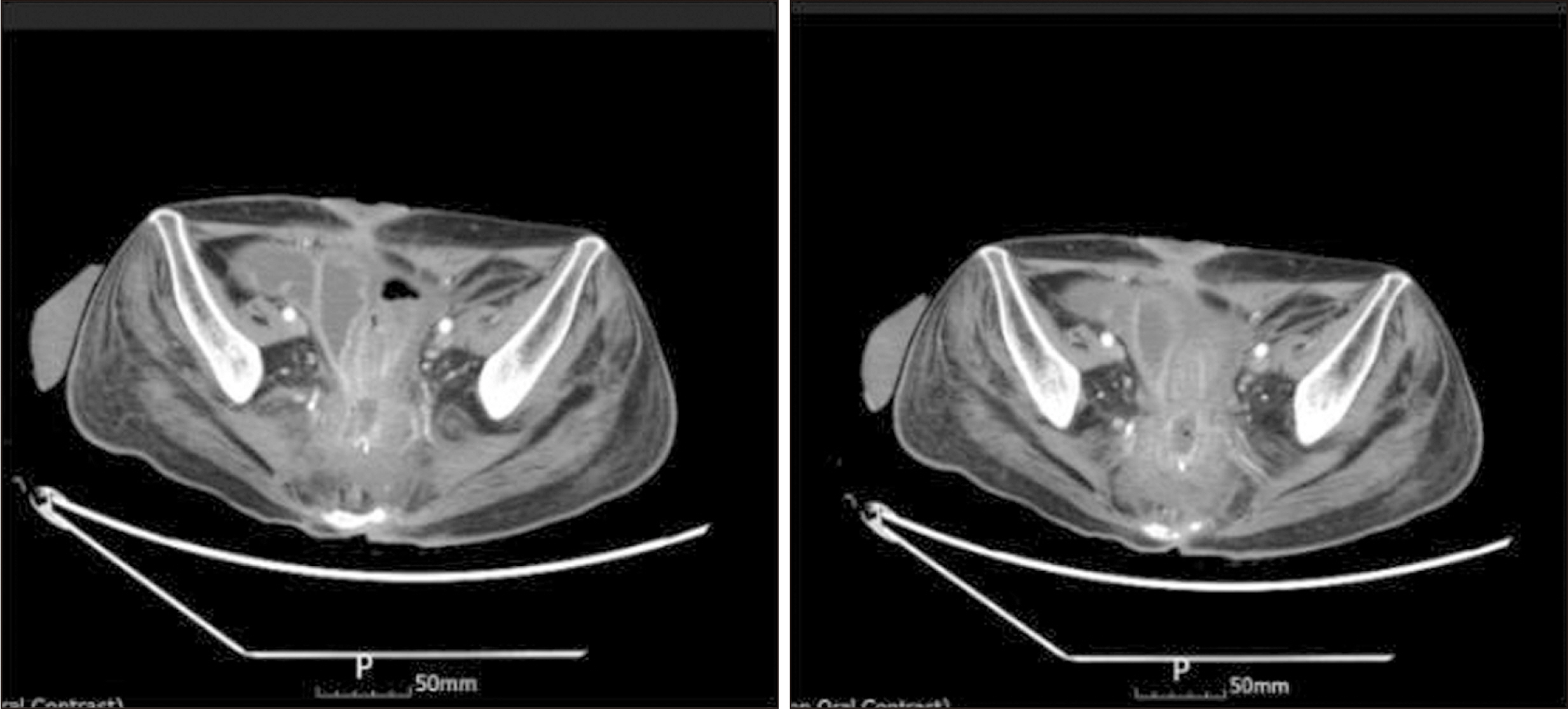

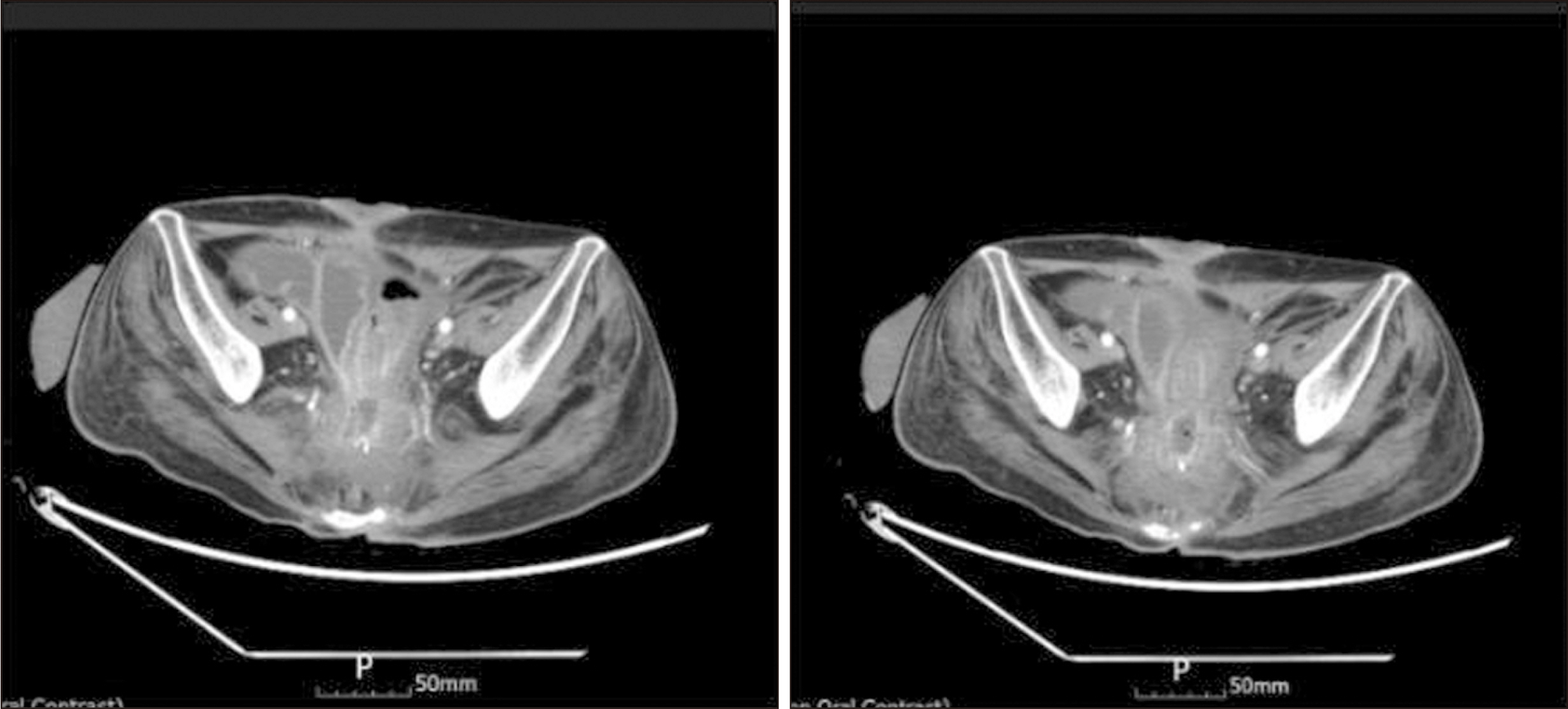

In May 2018, a 51-year-old male was admitted for treatment for a perivesical fistula between a presacral abscess and the rectus abdominis muscle that extended into the subcutaneous layer (Fig. 1). The patient had developed tetraplegia after a spinal cord injury in 1995. He had undergone a series of surgical procedures, including a laparoscopic total colectomy with end ileostomy for colonic inertia in February 2015, and a small bowel segmental resection with primary repair of the bladder due to SBO in September 2015. Since then, the patient had been hospitalized seven times for recurrent SBO and presacral abscess prior to the current hospital admission.

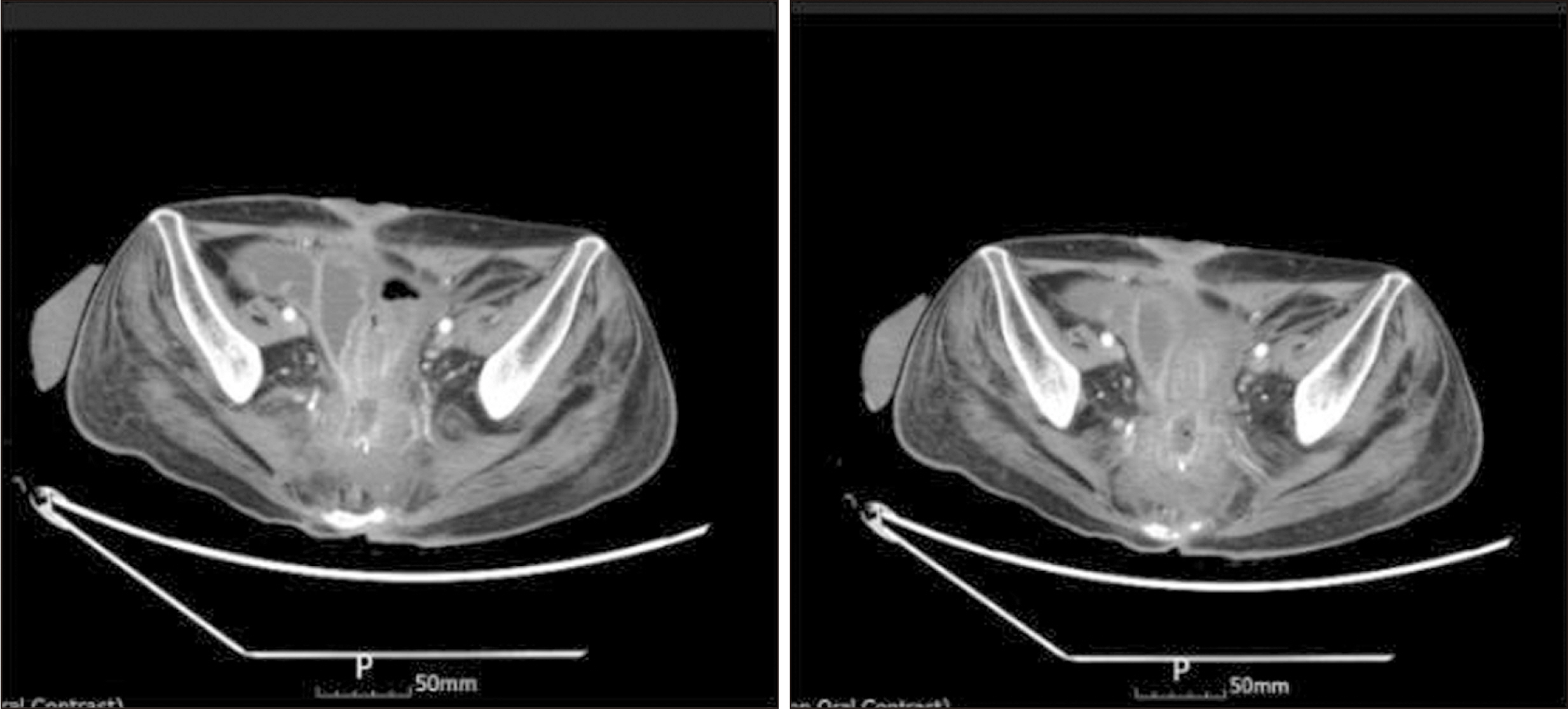

On the tenth day of hospitalization, he demonstrated SBO (Fig. 2), and was instructed to consume NPO. When the ileus improved about two weeks later, the patient attempted to resume a diet, but experienced immediately recurrent SBO. He eventually required over one month of fasting due to repeated episodes of SBO. While he adhered to NPO guidelines because of intestinal dysmotility, 1,450 mL of Winuf®peri (JW Pharmaceutical, Seoul, Korea) were given without any additional micronutrient supplement for over a month.

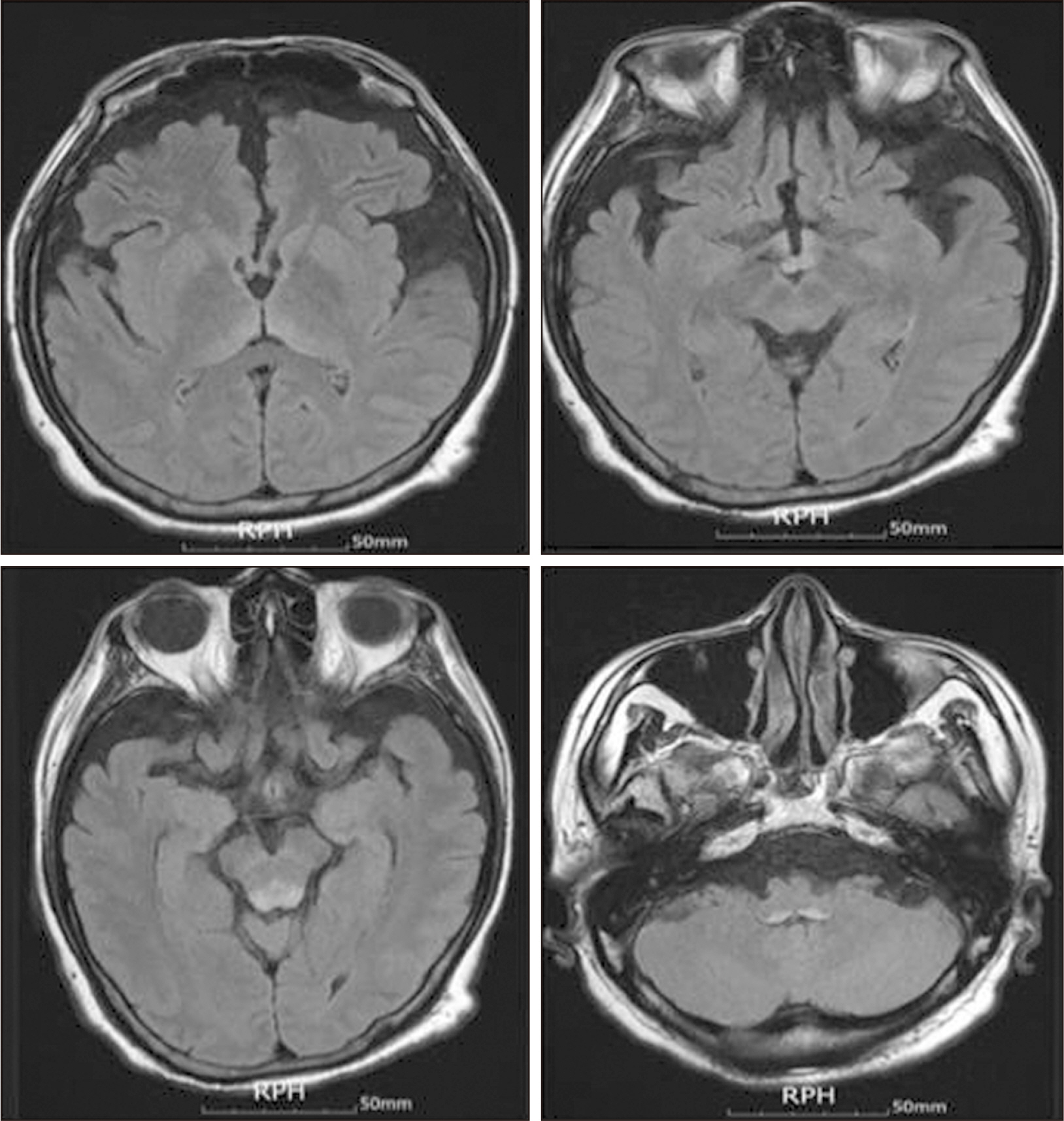

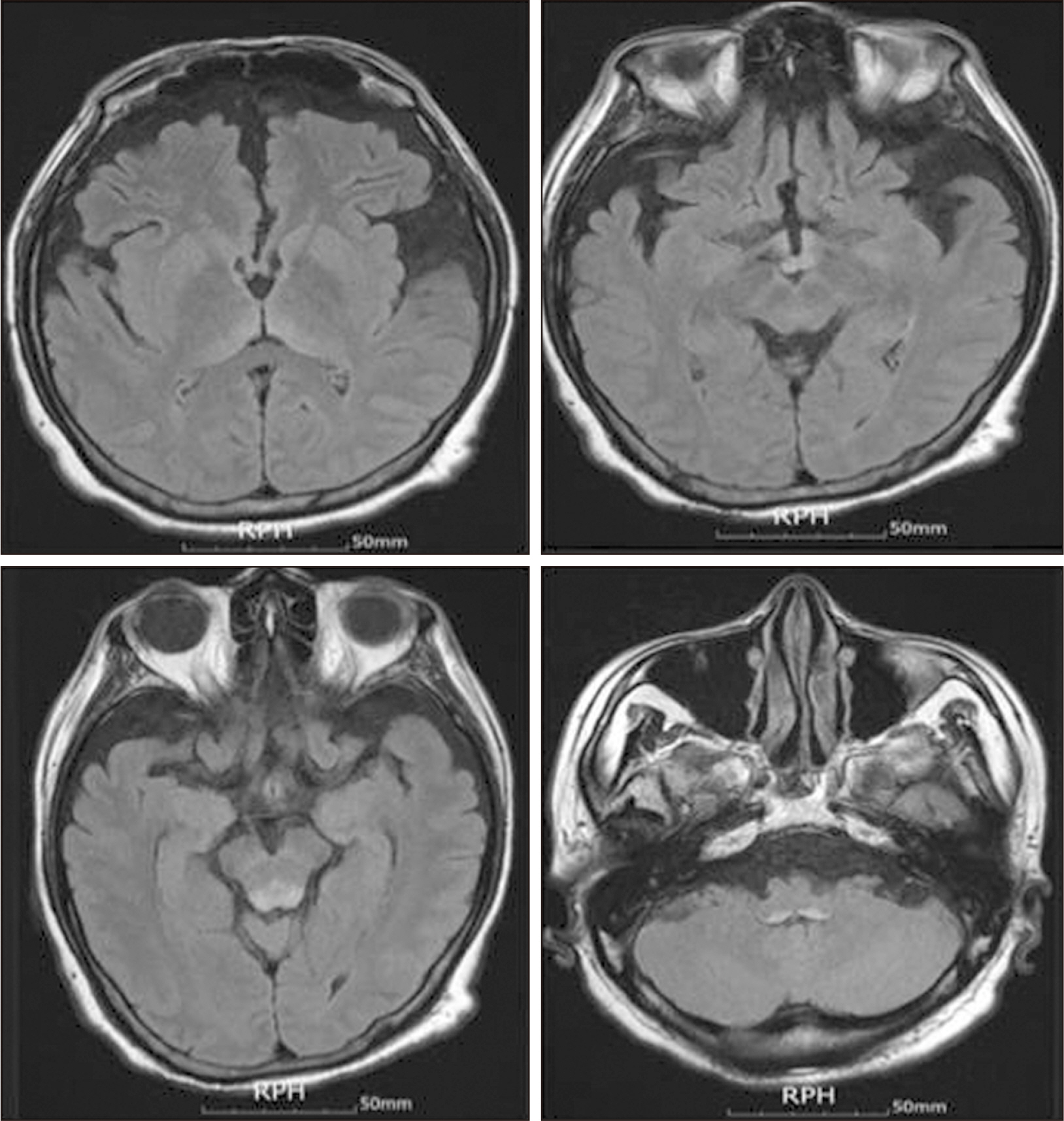

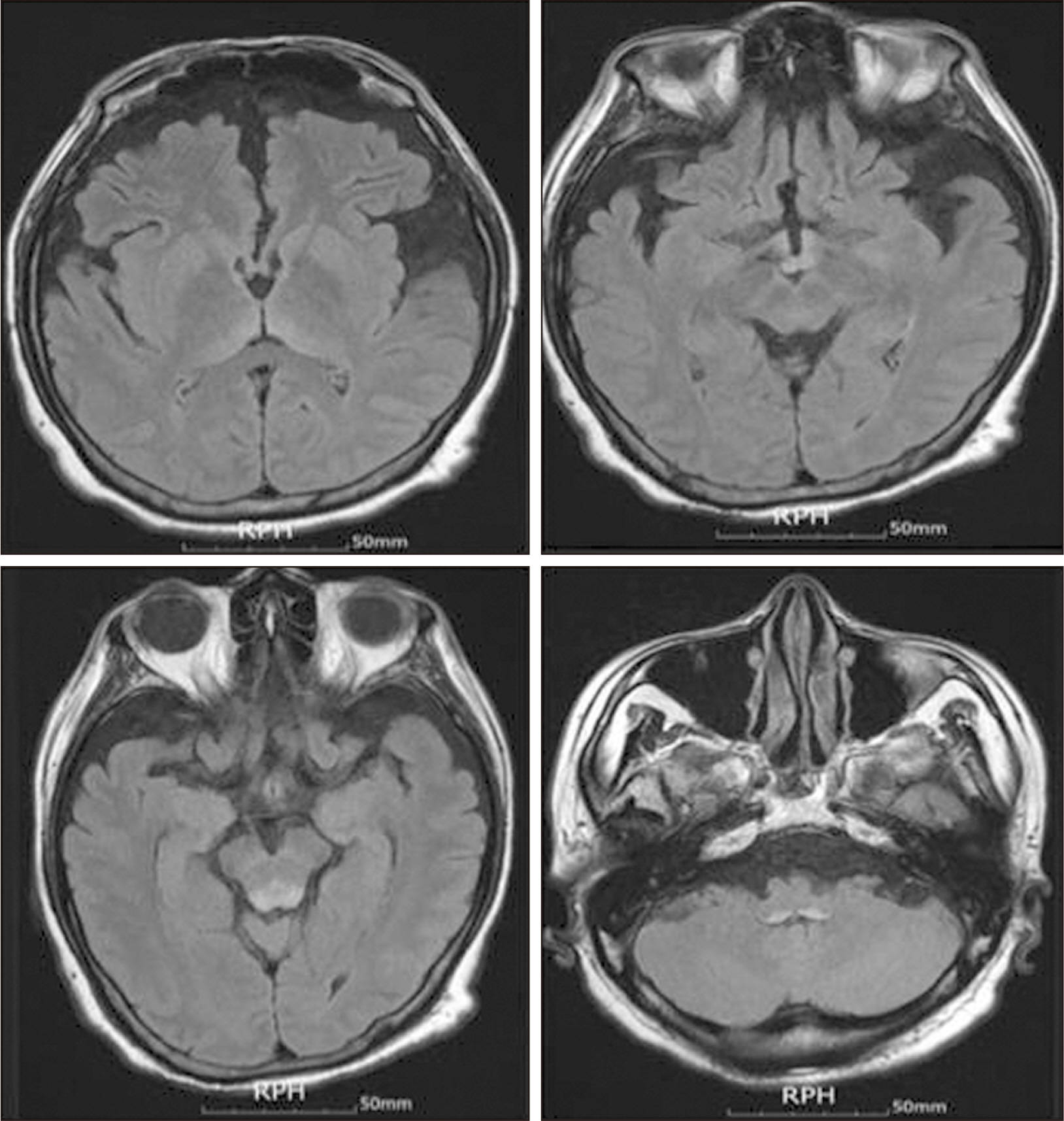

When the patient first was advised to be NPO, he weighed 57.7 kg and was 175 cm tall; his body mass index was 18.84 kg/m2. According to the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism’s practical guideline in chronic intestinal failure [13,14], the energy and protein requirements of this patient were 1,442.5 to 1,731.0 kcal/day (25~30 kcal/kg/day) and 46.16 to 80.78 g/day (0.8~1.4 g/kg/day), respectively, based on body weight of 57.7 kg. The energy intake provided by 1,450 mL of Winuf®peri (103 g glucose, 45.7 g amino acids, 40.8 g fat) was 1,004 kcal (58.0%~69.6% of the recommended energy intake). During a month of fasting, he lost about 5.4 kg, and he was deemed nutritionally at risk with a total score of 3 (weight loss >5% in a month: score 3) according to the Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 system [15,16]. On the thirtieth day of TPN administration, the patient complained of tinnitus and dizziness. In addition, he demonstrated gaze-evoked nystagmus and spontaneous left torsional nystagmus. His condition required a consultation with a neurologist because of the possibility of central vertigo. He was referred for a brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, which revealed several areas with abnormally high signals on T2-weighed and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images. These abnormalities were bilateral and found symmetrically in the medial thalami, mammillary bodies, periaqueductal area, tectum, substantia nigra, and dorsal medulla (Fig. 3). Laboratory results further revealed anemia (hemoglobin: 9.4 g/dL), and thrombocytopenia (platelet count: 73,000/μL), but liver and kidney function tests were normal. The blood vitamin B1 level was 48.8 nmol/L (normal range: 66.1~200.6 nmol/L). The patient’s ocular dysfunction and MRI findings suggested WE. The intravenous administration of 500 mg thiamine was immediately began every eight hours for three days, and 250 mg thiamine was given intravenously once daily for the next five days. His symptoms, such as tinnitus and dizziness, continued to improve slowly each day and resolved about eight days later. He eventually underwent surgery due to persistent SBO. However, after surgery, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus urosepsis led to the patient’s death.

CONCLUSION

Thiamine (vitamin B1) is a coenzyme that is essential for the maintenance of glucose metabolism in the central nervous system, for myelin continuity, and for the synthesis of acetylcholine, gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate [1]. The daily requirement of thiamine is 5 mg [3], and 0.5 mg thiamine per 1,000 kcal meal should be supplied to maintain thiamine-related functions [1]. Because the thiamine body reserves are approximately 30 mg, depletion of the body’s stores can develop within two to three weeks in patients receiving a strict thiamine-free diet [2,3,7].

Prolonged PN without adequate vitamin supplementation is known as another factor that contributes to the development of WE [1-3,17,18]. Among PN delivery systems, industrial three-compartment bags contain macronutrients and electrolytes in three separate compartments and require vitamin and trace-element supplementation just before their infusion [17,19]. In long-term TPN-fed patients, thiamine should be routinely added to PN mixtures [1,8]. It was reported that some clinicians erroneously thought that these bags contained adequate micronutrients and thus omitted their addition [17]. When WE is suspected, rapid treatment with high doses of thiamine is still a lifesaving measure to ameliorate WE [3,12]. The recommended dosage is 500 mg given intravenously three times a day for two to three days; additional treatment doses may be administered based on the clinical response [2,18,20].

Our patient developed WE on the thirtieth day of TPN administration without vitamin supplementation while fasting, and 500 mg thiamine was given intravenously every eight hours for three days immediately after his diagnosis. After that, 250 mg of thiamine were administered intravenously once daily for five consecutive days. At that time, the patient’s WE-related symptoms disappeared.

The current report raises the importance of proper vitamin supplementation during long-term TPN therapy, and prompt treatment with high-dose thiamine supplementation to prevent life-threatening neurological damage, when there is any clinical suspicion of WE. Closer attention should be paid to patients on long-term TPN therapy by a professional clinical nutrition support team in order to properly treat malnutrition and prevent TPN-related complications.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author of this manuscript has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FUNDING

None.

Fig. 1

Abdominopelvic computerized tomography scan showing perivesical fistula formation between a presacral abscess and the rectus muscle extending into the subcutaneous layer.

Fig. 2

Small bowel obstruction demonstrated on the tenth day of hospitalization on anteroposterior supine abdominal radiography.

Fig. 3

High signal in the medial thalami, mammillary bodies, periaqueductal area, tectum, substantia nigra, and dorsal medulla on T2-weighed (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) images.

- 1. Akçaboy ZN, Yağmurdur H, Baldemir R, Mutlu NM, Dikmen B. Wernicke's encephalopathy after longterm feeding with parenteral nutrition. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim 2014;42:96-9. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 2. Nishimoto A, Usery J, Winton JC, Twilla J. High-dose parenteral thiamine in treatment of Wernicke's encephalopathy: case series and review of the literature. In Vivo 2017;31:121-4. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 3. Jain K, Singh J, Jain A, Khera T. A case report of nonalcoholic Gayet-Wernicke encephalopathy: don't miss thiamine. A A Pract 2020;14:e01230. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 4. Ota Y, Capizzano AA, Moritani T, Naganawa S, Kurokawa R, Srinivasan A. 2020;Comprehensive review of Wernicke encephalopathy: pathophysiology, clinical symptoms and imaging findings. Jpn J Radiol 38:809-20. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 5. Mantero V, Rifino N, Costantino G, Farina A, Pozzetti U, Sciacco M, et al. Non-alcoholic beriberi, Wernicke encephalopathy and long-term eating disorder: case report and a mini-review. Eat Weight Disord 2021;26:729-32. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 6. Dilber B, Kamaşak T, Eyüboğlu İ, Kola M, Uysal AT, Saruhan H, et al. Wernicke's encephalopathy manifesting with diplopia after ileojejunostomy: report of a pediatric case with Hirschsprung disease. Turk J Pediatr 2020;62:310-4. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 7. Theodoreson MD, Zykaite A, Haley M, Meena S. Case of non-alcoholic Wernicke's encephalopathy. BMJ Case Rep 2019;12:e230763. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Francini-Pesenti F, Brocadello F, Manara R, Santelli L, Laroni A, Caregaro L. 2009;Wernicke's syndrome during parenteral feeding: not an unusual complication. Nutrition 25:142-6. ArticlePubMed

- 9. Hahn JS, Berquist W, Alcorn DM, Chamberlain L, Bass D. Wernicke encephalopathy and beriberi during total parenteral nutrition attributable to multivitamin infusion shortage. Pediatrics 1998;101:E10.ArticlePDF

- 10. Fedeli P, Justin Davies R, Cirocchi R, Popivanov G, Bruzzone P, Giustozzi M. Total parenteral nutrition-induced Wernicke's encephalopathy after oncologic gastrointestinal surgery. Open Med (Wars) 2020;15:709-13. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Bismi S, Dhanya D. A literature review on importance of parenteral nutrition safety process. World J Pharm Res 2021;10:173-86.

- 12. Oudman E, Wijnia JW, Oey MJ, van Dam M, Postma A. Wernicke's encephalopathy in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Nutrition 2021;86:111182. ArticlePubMed

- 13. Cuerda C, Pironi L, Arends J, Bozzetti F, Gillanders L, Jeppesen PB, et al. Home Artificial Nutrition & Chronic Intestinal Failure Special Interest Group of ESPEN. 2021;ESPEN practical guideline: clinical nutrition in chronic intestinal failure. Clin Nutr 40:5196-220. ArticlePubMed

- 14. Staun M, Pironi L, Bozzetti F, Baxter J, Forbes A, Joly F, et al. ESPEN. ESPEN guidelines on parenteral nutrition: home parenteral nutrition (HPN) in adult patients. Clin Nutr 2009;28:467-79. ArticlePubMed

- 15. Kondrup J, Allison SP, Elia M, Vellas B, Plauth M. Educational and Clinical Practice Committee, European Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ESPEN). ESPEN guidelines for nutrition screening 2002. Clin Nutr 2003;22:415-21. ArticlePubMed

- 16. Kondrup J, Rasmussen HH, Hamberg O, Stanga Z. Ad Hoc ESPEN Working Group. Nutritional risk screening (NRS 2002): a new method based on an analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clin Nutr 2003;22:321-36. ArticlePubMed

- 17. Francini-Pesenti F, Brocadello F, Famengo S, Nardi M, Caregaro L. Wernicke's encephalopathy during parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2007;31:69-71. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 18. Stawny M, Gostyńska A, Olijarczyk R, Jelińska A, Ogrodowczyk M. Stability of high-dose thiamine in parenteral nutrition for treatment of patients with Wernicke's encephalopathy. Clin Nutr 2020;39:2929-32. ArticlePubMed

- 19. Gervasio J. Compounding vs standardized commercial parenteral nutrition product: pros and cons. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2012;36(2 Suppl):40S-41S. PubMed

- 20. Thomson AD, Guerrini I, Marshall EJ. 2012;The evolution and treatment of Korsakoff's syndrome: out of sight, out of mind? Neuropsychol Rev 22:81-92. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

References

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

Development of Wernicke’s Encephalopathy during Total Parenteral Nutrition Therapy without Additional Multivitamin Supplementation in a Patient with Intestinal Obstruction: A Case Report

Fig. 1

Abdominopelvic computerized tomography scan showing perivesical fistula formation between a presacral abscess and the rectus muscle extending into the subcutaneous layer.

Fig. 2

Small bowel obstruction demonstrated on the tenth day of hospitalization on anteroposterior supine abdominal radiography.

Fig. 3

High signal in the medial thalami, mammillary bodies, periaqueductal area, tectum, substantia nigra, and dorsal medulla on T2-weighed (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) images.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Development of Wernicke’s Encephalopathy during Total Parenteral Nutrition Therapy without Additional Multivitamin Supplementation in a Patient with Intestinal Obstruction: A Case Report

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite