Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Ann Clin Nutr Metab > Volume 16(2); 2024 > Article

- Original Article Prognostic significance of serum creatinine and sarcopenia for 5-year overall survival in patients with colorectal cancer in Korea: a comparative study

-

Jiahn Choi1

, Hye Sun Lee2

, Hye Sun Lee2 , Jeonghyun Kang3

, Jeonghyun Kang3

-

Annals of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism 2024;16(2):66-77.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.15747/ACNM.2024.16.2.66

Published online: August 1, 2024

1Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

2Biostatistics Collaboration Unit, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

3Department of Surgery, Gangnam Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- Corresponding author: Jeonghyun Kang, email: ravic@naver.com

Medical student.

© 2024 The Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition · The Korean Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 643 Views

- 13 Download

Abstract

-

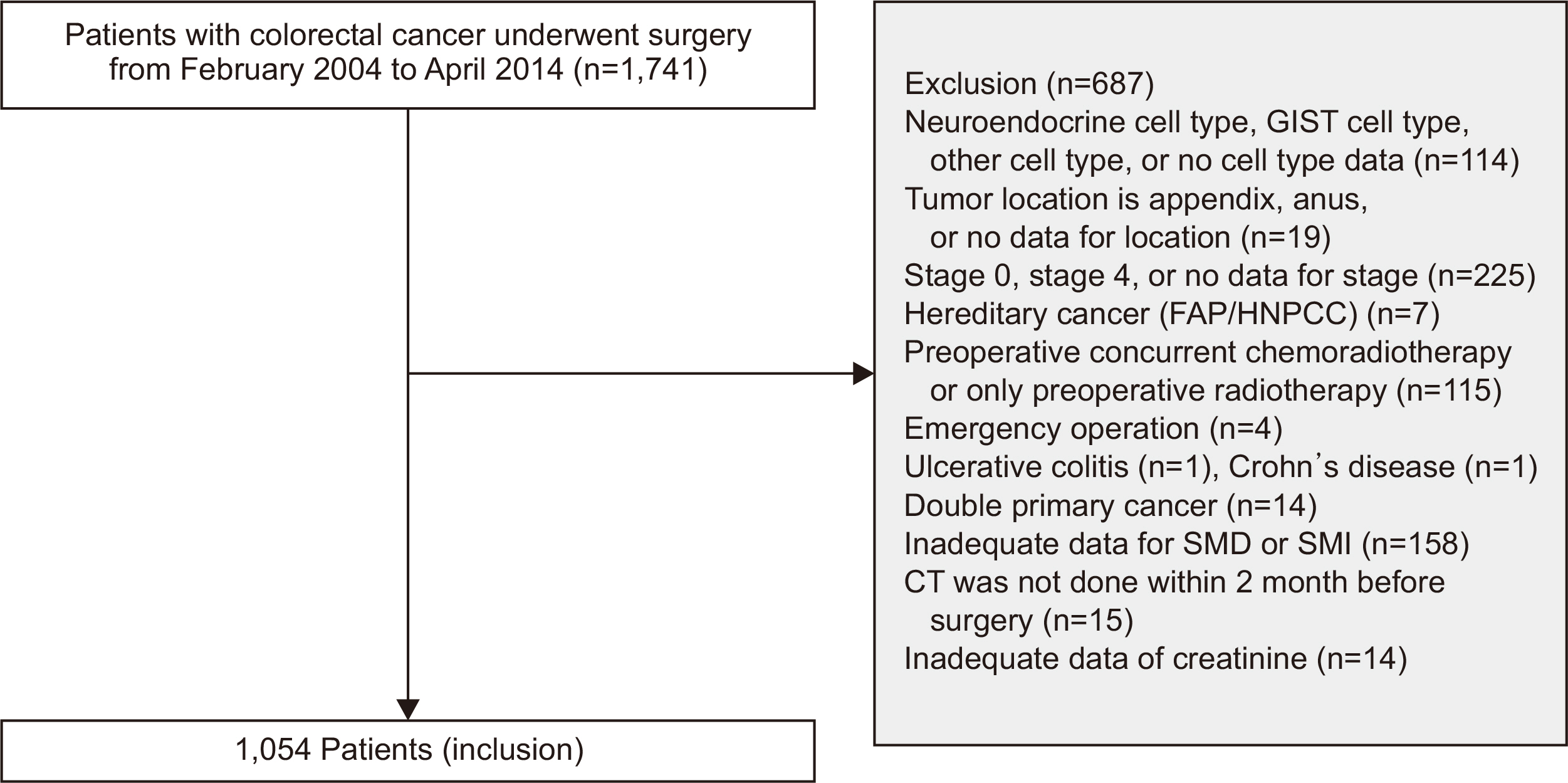

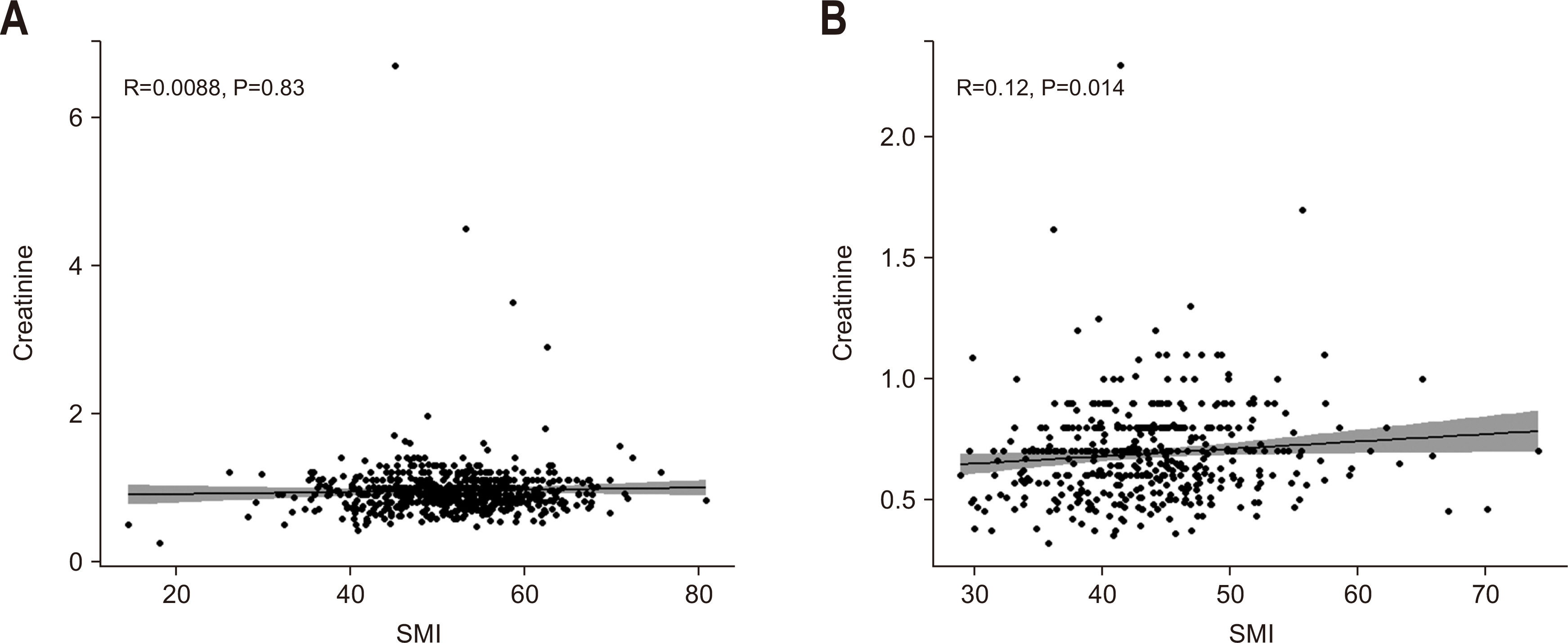

Purpose Previous studies have demonstrated that the serum creatinine level and skeletal muscle index (SMI) (correlated with the overall survival [OS] of patients with colorectal cancer [CRC]). However, the combined significance of these 2 factors is not fully understood. The goal of this study was to investigate the prognostic potential of the combination of these two factors in patients with CRC.

-

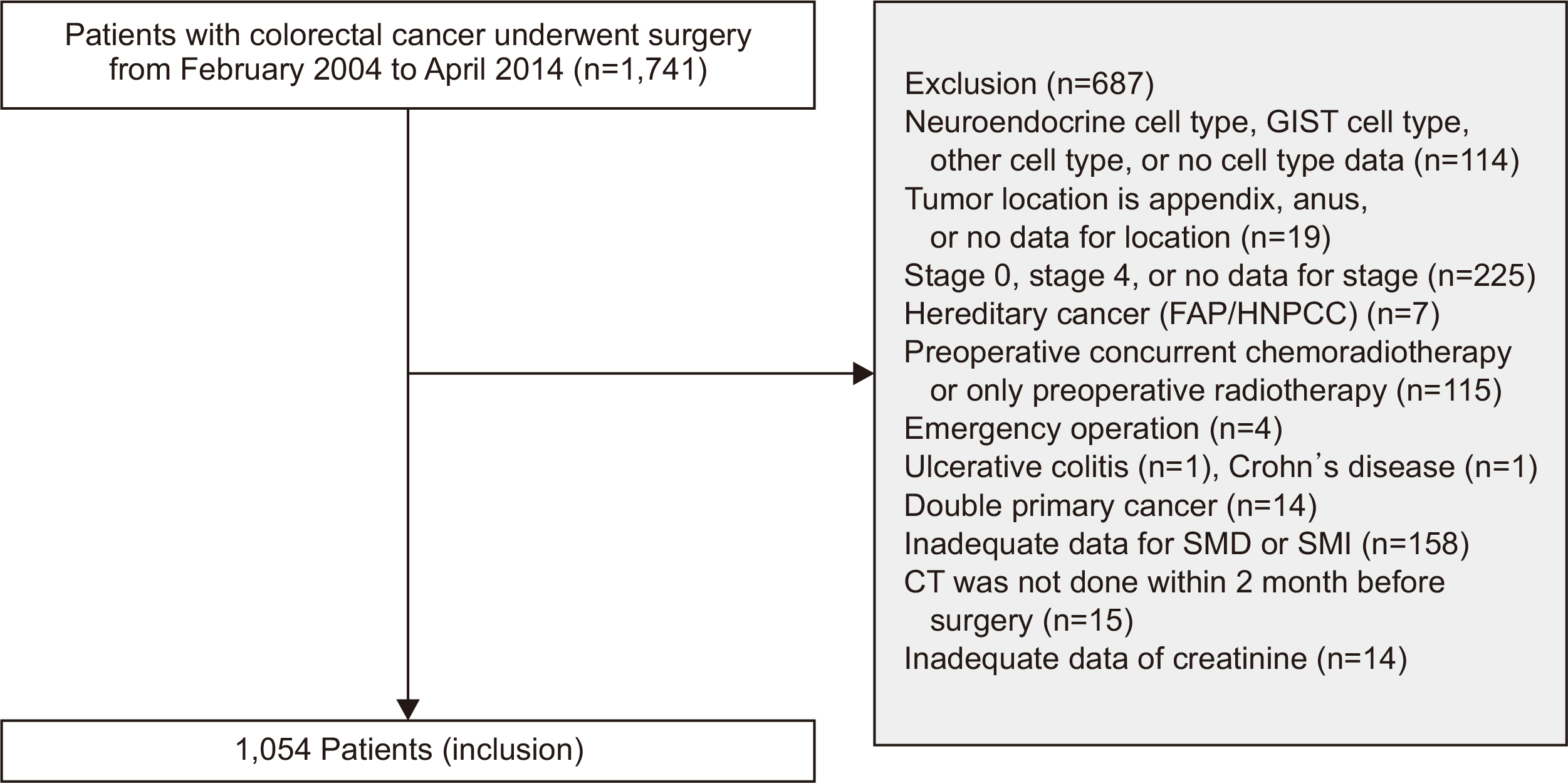

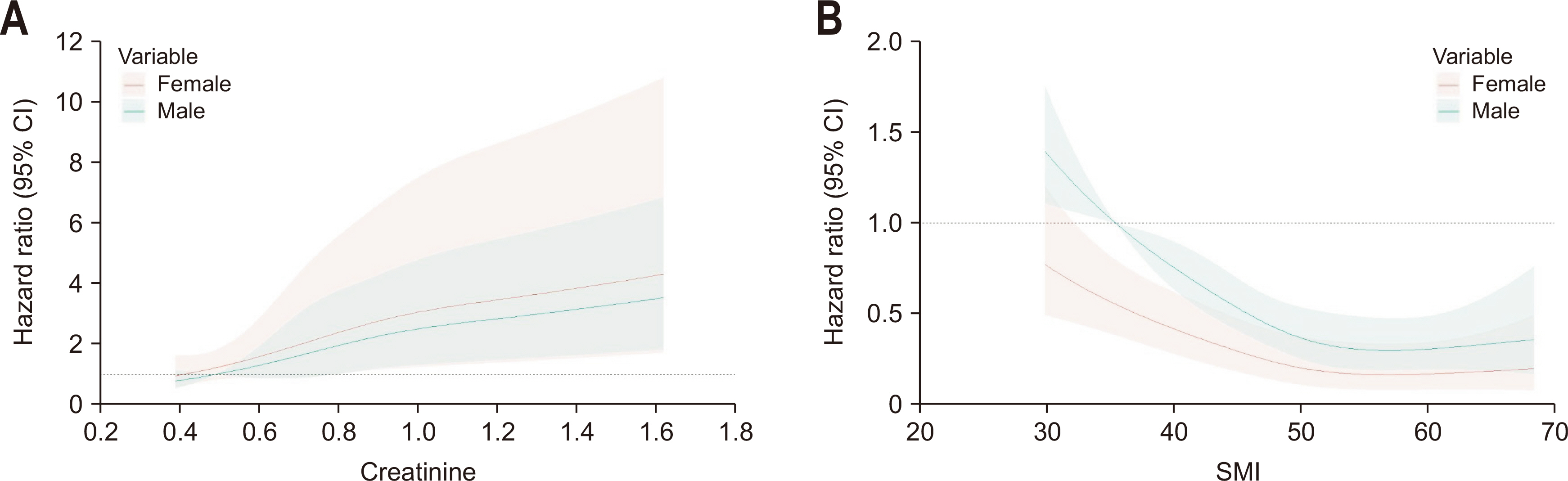

Methods The patients were categorized into subgroups based on preoperative serum creatinine level, with a cut-off value of 1.01 mg/dL for males and 0.80 mg/dL for females. The patients were further categorized into 4 groups based on SMI. Data were analyzed using the Cox proportional hazards model and Harrell’s concordance index (C-index).

-

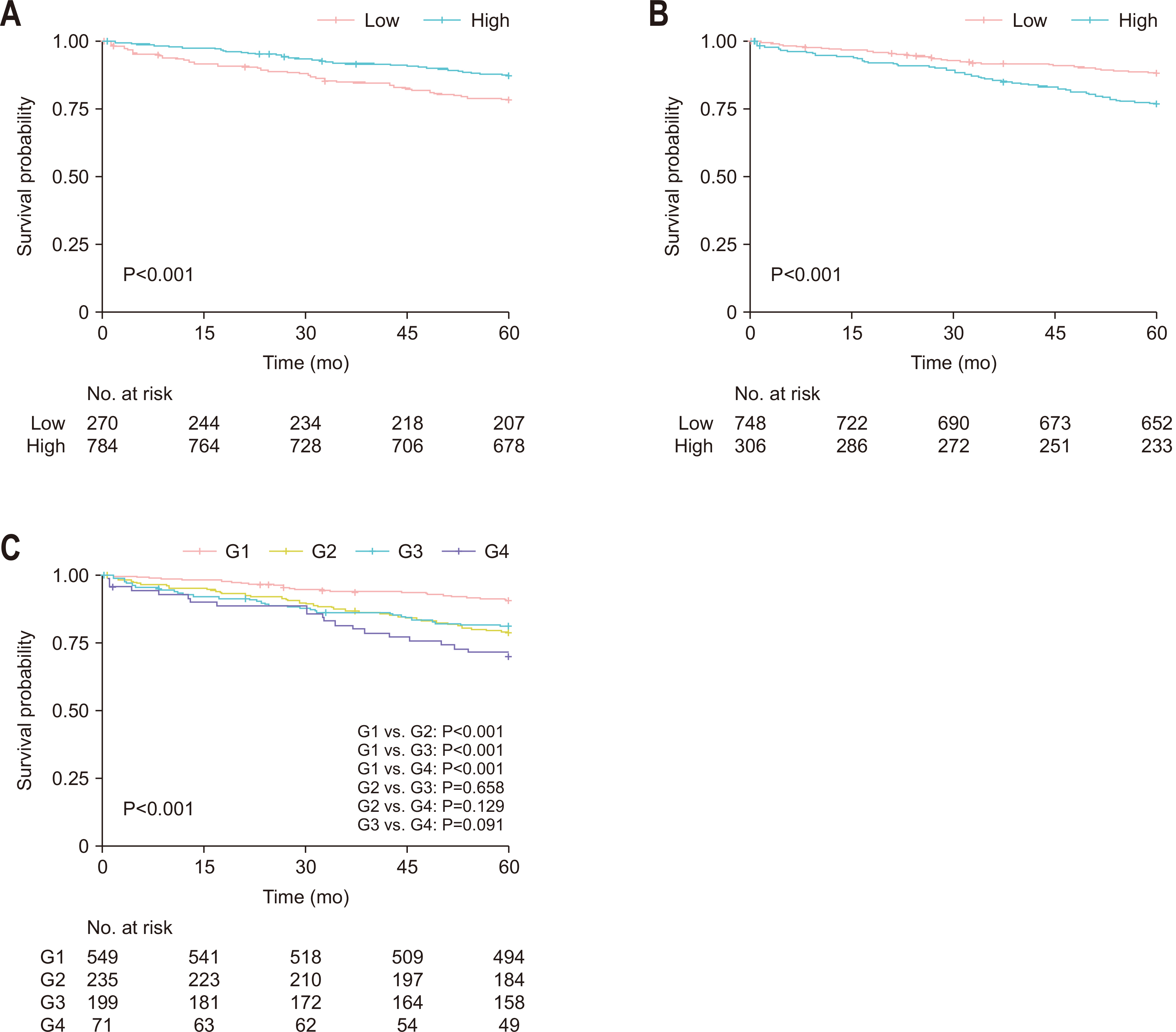

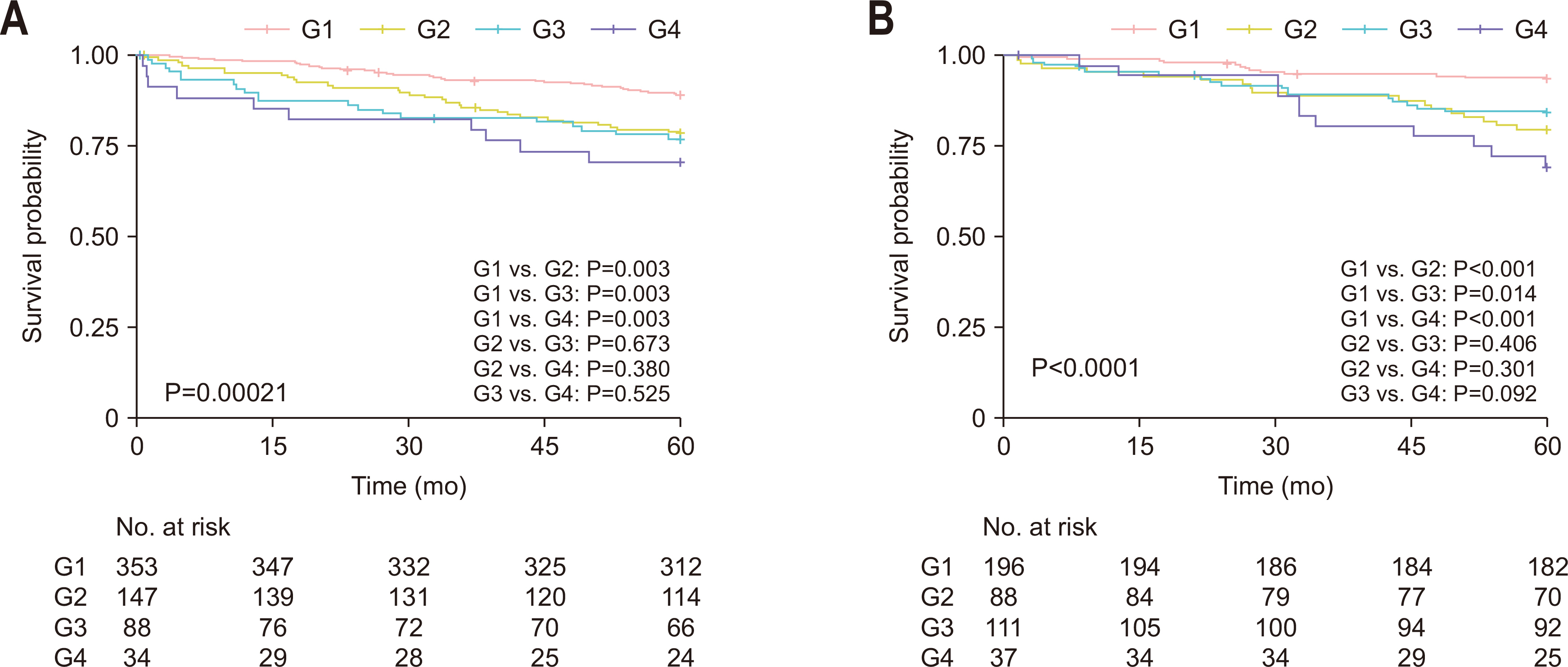

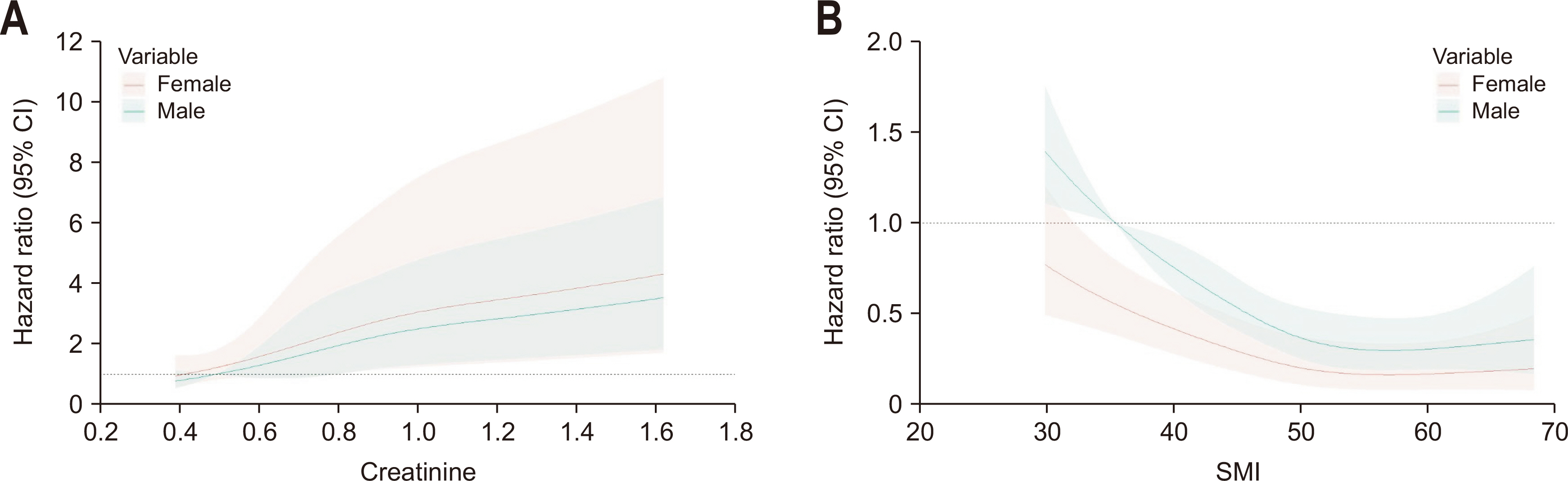

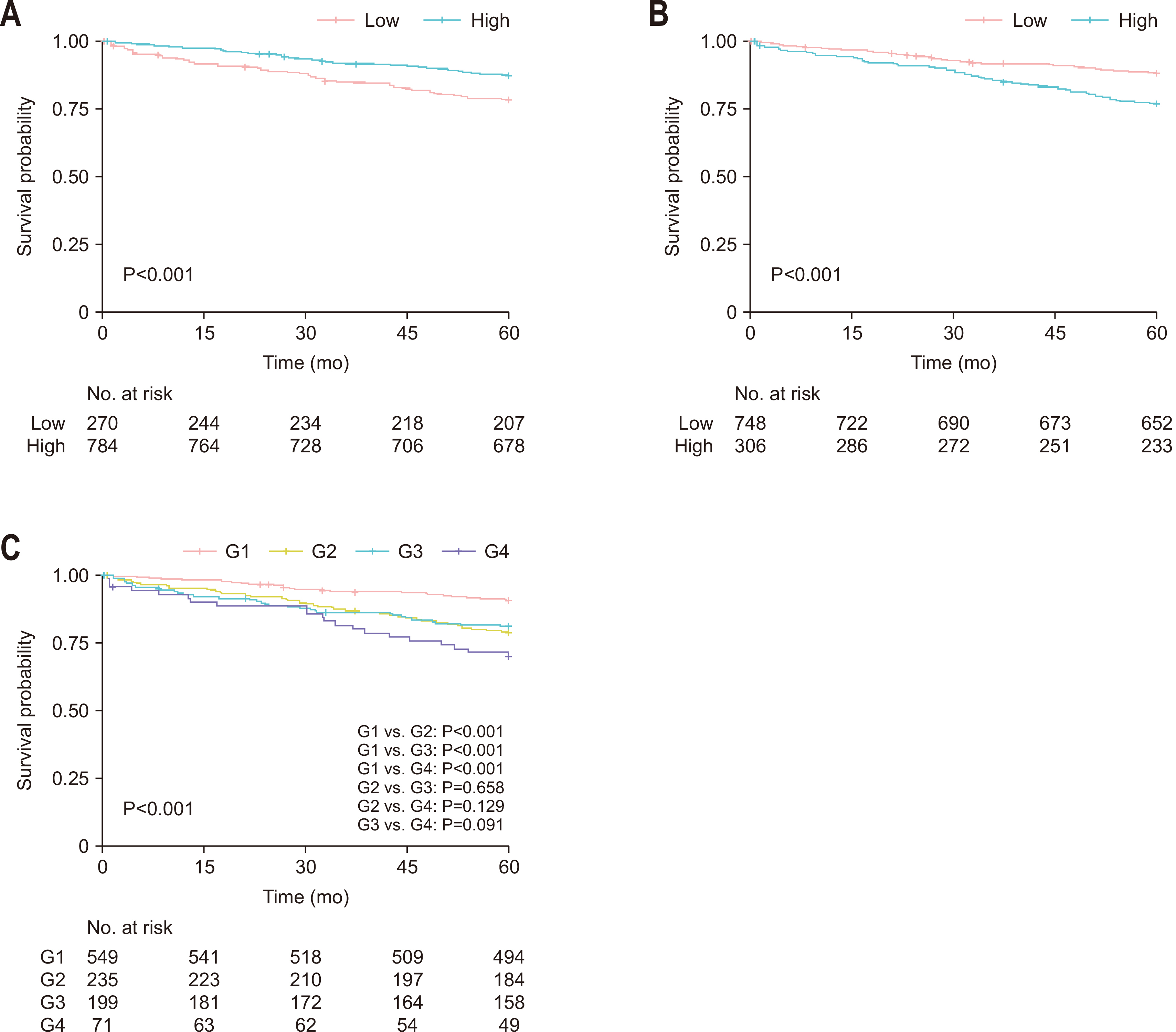

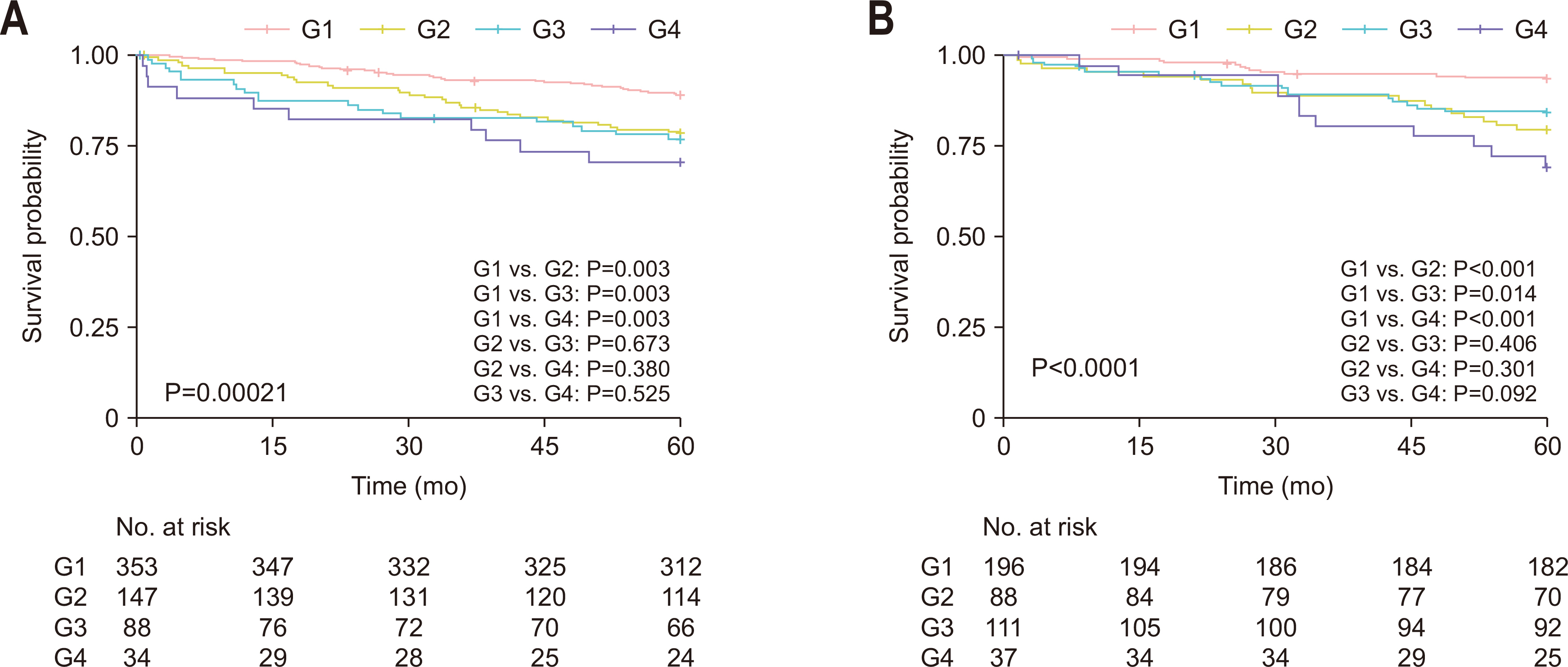

Results Poor 5-year OS was observed in patients with high SMI and high serum creatinine levels (hazard ratio [HR]=1.676, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.110–2.529, P=0.013), low SMI and low serum creatinine levels (HR=1.916, 95% CI=1.249–2.938, P=0.002), and low SMI and high serum creatinine levels (HR=2.172, 95% CI=1.279–3.687, P=0.004) compared to those of patients with high SMI and low serum creatinine levels. Grouping patients based on both SMI and serum creatinine levels led to improved prognostic stratification (C-index, 0.626; 95% CI=0.587–0.666) compared to grouping based on SMI (CI difference=0.062, 95% CI=0.031–0.103, P=0.0011) or serum creatinine (CI difference=0.043, 95% CI=0.017–0.081, P=0.0072) alone.

-

Conclusion Incorporating both SMI and serum creatinine levels enhances the prognostic stratification for 5-year OS in patients with CRC, surpassing the prognostic power of grouping solely based on SMI or creatinine.

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Supplementary materials

Acknowledgements

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: JC, JK. Data curation: HSL, JK. Formal analysis: HSL. Funding acquisition: JK. Investigation: HSL, JK. Methodology: JC, JK. Project administration: JK, JK. Resources: HSL, JK. Software: JC, HSL. Supervision: JK. Validation: JK. Visualization: JC. Writing – original draft: JC. Writing – review & editing: JC, JK.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2022R1F1A1074811).

Data availabity

Due to the retrospective nature of this study and the utilization of patient data, we do not have ethical approval to publish the raw data or transfer it from our hospital electronic medical server.

Values are presented as number (%) or mean±standard deviation.

SMI = skeletal muscle index; BMI = body mass index; CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen; G1 = no sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; G2 = no sarcopenia with high serum creatinine levels; G3 = sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; MC = mucinous adenocarcinoma; SRC = signet-ring cell; LVI = lymphovascular invasion; SMD = skeletal muscle radiodensity; HU = Hounsfield unit.

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; BMI = body mass index; CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen; G1 = no sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; G2 = no sarcopenia with high serum creatinine levels; G3 = sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; MC = mucinous adenocarcinoma; SRC = signet-ring cell; LVI = lymphovascular invasion; SMI = skeletal muscle index; SMD = skeletal muscle radiodensity; HU = Hounsfield unit; G4 = sarcopenia with high serum creatinine level.

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; BMI = body mass index; CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen; G1 = no sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; G2 = no sarcopenia with high serum creatinine levels; G3 = sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; MC = mucinous adenocarcinoma; SRC = signet-ring cell; SMD = skeletal muscle radiodensity; HU = Hounsfield unit; G4 = sarcopenia with high serum creatinine level.

- 1. Baidoun F, Elshiwy K, Elkeraie Y, Merjaneh Z, Khoudari G, Sarmini MT, et al. Colorectal cancer epidemiology: recent trends and impact on outcomes. Curr Drug Targets 2021;22:998-1009. ArticlePubMed

- 2. Kang MJ, Jung KW, Bang SH, Choi SH, Park EH, Yun EH, et al. Community of Population-Based Regional Cancer Registries. Cancer Statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2020. Cancer Res Treat 2023;55:385-99. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 3. Ubachs J, Ziemons J, Minis-Rutten IJG, Kruitwagen RFPM, Kleijnen J, Lambrechts S, et al. Sarcopenia and ovarian cancer survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019;10:1165-74. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 4. Feliciano EMC, Kroenke CH, Meyerhardt JA, Prado CM, Bradshaw PT, Kwan ML, et al. Association of systemic inflammation and sarcopenia with survival in nonmetastatic colorectal cancer: results from the C SCANS Study. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:e172319. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 5. Jogiat UM, Bédard ELR, Sasewich H, Turner SR, Eurich DT, Filafilo H, et al. 2022;Sarcopenia reduces overall survival in unresectable oesophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 13:2630-6. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 6. Kashani K, Rosner MH, Ostermann M. Creatinine: from physiology to clinical application. Eur J Intern Med 2020;72:9-14. ArticlePubMed

- 7. Dudani S, Marginean H, Gotfrit J, Tang PA, Monzon JG, Dennis K, et al. The impact of chronic kidney disease in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Dis Colon Rectum 2021;64:1471-8. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Obara S, Koyama F, Kuge H, Nakamoto T, Ikeda N, Iwasa Y, et al. Effect of preoperative asymptomatic renal dysfunction on the clinical course after colectomy for colon cancer. Surg Today 2022;52:106-13. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 9. Chan JCY, Diakos CI, Engel A, Chan DLH, Pavlakis N, Gill A, et al. Serum bicarbonate is a marker of peri-operative mortality but is not associated with long term survival in colorectal cancer. PLoS One 2020;15:e0228466. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. Watanabe A, Oshikiri T, Sawada R, Harada H, Urakawa N, Goto H, et al. 2022;Actual sarcopenia reflects poor prognosis in patients with esophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 29:3670-81. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 11. Martin L, Birdsell L, Macdonald N, Reiman T, Clandinin MT, McCargar LJ, et al. Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:1539-47. ArticlePubMed

- 12. Camp RL, Dolled-Filhart M, Rimm DL. X-tile: a new bio-informatics tool for biomarker assessment and outcome-based cut-point optimization. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:7252-9. PubMed

- 13. Oh RK, Ko HM, Lee JE, Lee KH, Kim JY, Kim JS. Clinical impact of sarcopenia in patients with colon cancer undergoing laparoscopic surgery. Ann Surg Treat Res 2020;99:153-60. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 14. van Vugt JLA, Coebergh van den Braak RRJ, Lalmahomed ZS, Vrijland WW, Dekker JWT, Zimmerman DDE, et al. Impact of low skeletal muscle mass and density on short and long-term outcome after resection of stage I-III colorectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2018;44:1354-60. ArticlePubMed

- 15. Han JS, Ryu H, Park IJ, Kim KW, Shin Y, Kim SO, et al. Association of body composition with long-term survival in non-metastatic rectal cancer patients. Cancer Res Treat 2020;52:563-72. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 16. McGovern J, Dolan RD, Horgan PG, Laird BJ, McMillan DC. Computed tomography-defined low skeletal muscle index and density in cancer patients: observations from a systematic review. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021;12:1408-17. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 17. Delgado C, Johansen KL. Revisiting serum creatinine as an indicator of muscle mass and a predictor of mortality among patients on hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020;35:2033-5. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 18. Yamada S, Arase H, Taniguchi M, Kitazono T, Nakano T. Comparison of the predictability of serum creatinine-based surrogates of skeletal muscle mass for all-cause mortality in patients receiving hemodialysis: creatinine generation rate and creatinine index. Clin Exp Nephrol 2022;26:488-9. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 19. Kim SW, Jung HW, Kim CH, Kim KI, Chin HJ, Lee H. A new equation to estimate muscle mass from creatinine and cystatin C. PLoS One 2016;11:e0148495. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 20. Patel SS, Molnar MZ, Tayek JA, Ix JH, Noori N, Benner D, et al. 2013;Serum creatinine as a marker of muscle mass in chronic kidney disease: results of a cross-sectional study and review of literature. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 4:19-29. ArticlePubMed

- 21. das Neves W, Alves CRR, de Souza Borges AP, de Castro G Jr. Serum creatinine as a potential biomarker of skeletal muscle atrophy in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Front Physiol 2021;12:625417. PubMedPMC

- 22. Tabara Y, Okada Y, Ochi M, Ohyagi Y, Igase M. 2021;Different associations of skeletal muscle mass index and creatinine-to-cystatin C ratio with muscle mass and myosteatosis: the J-SHIPP study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 22:2600-2. ArticlePubMed

- 23. Nishida K, Hashimoto Y, Kaji A, Okamura T, Sakai R, Kitagawa N, et al. Creatinine/(cystatin C × body weight) ratio is associated with skeletal muscle mass index. Endocr J 2020;67:733-40. ArticlePubMed

- 24. Yang M, Zhang Q, Ruan GT, Tang M, Zhang X, Song MM, et al. Association between serum creatinine concentrations and overall survival in patients with colorectal cancer: a multi-center cohort study. Front Oncol 2021;11:710423. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 25. Lafleur J, Hefler-Frischmuth K, Grimm C, Schwameis R, Gensthaler L, Reiser E, et al. 2018;Prognostic value of serum creatinine levels in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Anticancer Res 38:5127-30. ArticlePubMed

- 26. Schwameis R, Postl M, Bekos C, Hefler L, Reinthaller A, Seebacher V, et al. Prognostic value of serum creatine level in patients with vulvar cancer. Sci Rep 2019;9:11129. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 27. Li H, Zhang X, Xu G, Wang X, Zhang C. 2009;Determination of reference intervals for creatinine and evaluation of creatinine-based estimating equation for Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Chim Acta 403:87-91. ArticlePubMed

References

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

Fig. 1

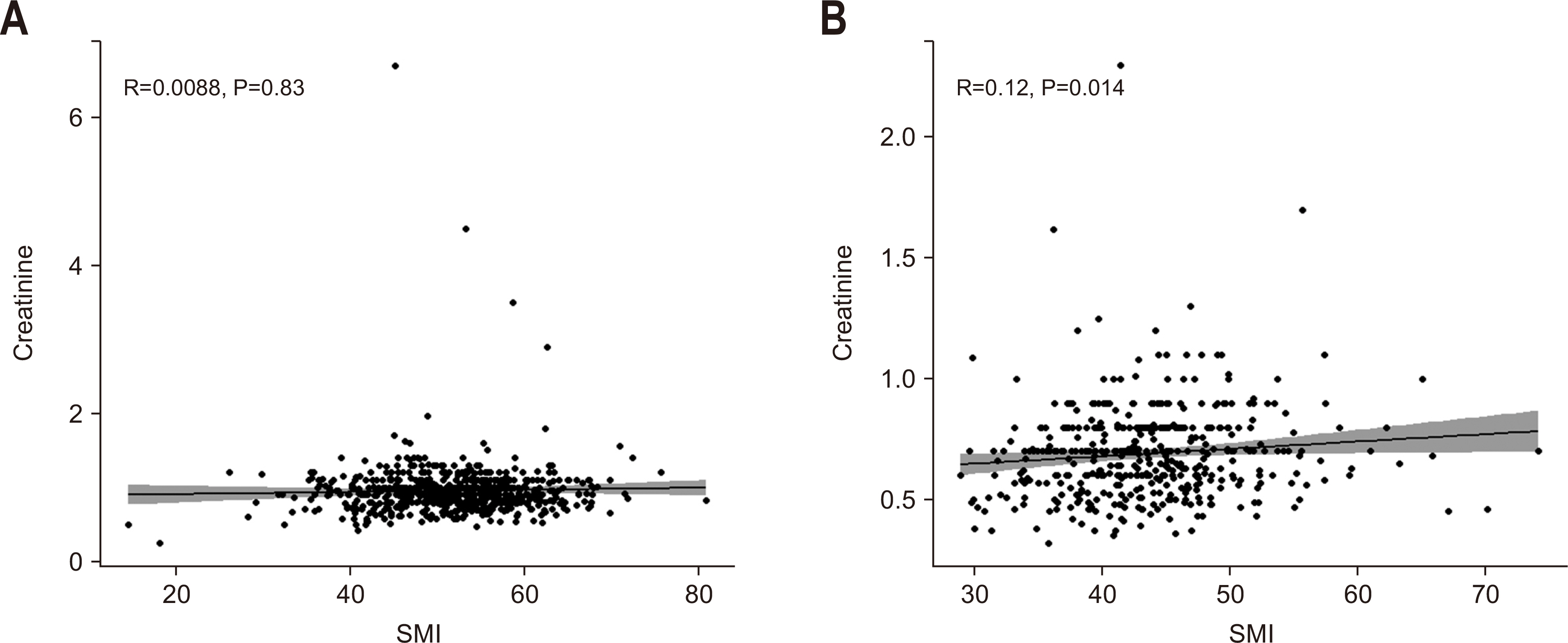

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Patient characteristics according to the skeletal muscle index and serum creatinine level

| Variable | Categorization | Low SMI (n=270) | High SMI (n=784) | P-value | Low creatinine (n=748) | High creatinine (n=306) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 148 (54.8) | 284 (36.2) | 307 (41.0) | 125 (40.8) | ||

| Male | 122 (45.2) | 500 (63.8) | <0.001 | 441 (59.0) | 181 (59.2) | >0.999 | |

| Age (yr) | <70 | 168 (62.2) | 545 (69.5) | 546 (73.0) | 167 (54.6) | ||

| ≥70 | 102 (37.8) | 239 (30.5) | 0.033 | 202 (27.0) | 139 (45.4) | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | No | 226 (83.7) | 625 (79.7) | 622 (83.2) | 229 (74.8) | ||

| Yes | 44 (16.3) | 159 (20.3) | 0.179 | 126 (16.8) | 77 (25.2) | 0.003 | |

| Hypertension | No | 168 (62.2) | 436 (55.6) | 469 (62.7) | 135 (44.1) | ||

| Yes | 102 (37.8) | 348 (44.4) | 0.068 | 279 (37.3) | 171 (55.9) | <0.001 | |

| Smoking | No | 198 (73.3) | 528 (67.3) | 508 (67.9) | 218 (71.2) | ||

| Yes | 72 (26.7) | 256 (32.7) | 0.079 | 240 (32.1) | 88 (28.8) | 0.324 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.8±3.2 | 24.1±2.8 | <0.001 | 23.4±3.0 | 23.7±3.2 | 0.226 | |

| CEA (ng/mL) | <5 | 181 (67.0) | 548 (69.9) | 515 (68.9) | 214 (69.9) | ||

| ≥5 | 75 (27.8) | 202 (25.8) | 193 (25.8) | 84 (27.5) | |||

| Unknown | 14 (5.2) | 34 (4.3) | 0.649 | 40 (5.3) | 8 (2.6) | 0.148 | |

| Tumor location | Colon | 201 (74.4) | 534 (68.1) | 528 (70.6) | 207 (67.6) | ||

| Rectum | 69 (25.6) | 250 (31.9) | 0.061 | 220 (29.4) | 99 (32.4) | 0.385 | |

| Histologic grade | G1 & G2 | 249 (92.2) | 723 (92.2) | 691 (92.4) | 281 (91.8) | ||

| G3 & MC & SRC | 21 (7.8) | 61 (7.8) | >0.99 | 57 (7.6) | 25 (8.2) | 0.861 | |

| LVI | Absent | 181 (67.0) | 550 (70.2) | 524 (70.1) | 207 (67.6) | ||

| Present | 58 (21.5) | 157 (20.0) | 152 (20.3) | 63 (20.6) | |||

| Unknown | 31 (11.5) | 77 (9.8) | 0.597 | 72 (9.6) | 36 (11.8) | 0.560 | |

| Lymph nodes | <12 | 39 (14.4) | 125 (15.9) | 90 (12.0) | 74 (24.2) | ||

| ≥12 | 231 (85.6) | 659 (84.1) | 0.625 | 658 (88.0) | 232 (75.8) | <0.001 | |

| Stage | I | 56 (20.7) | 213 (27.2) | 201 (26.9) | 68 (22.2) | ||

| II | 96 (35.6) | 252 (32.1) | 248 (33.2) | 100 (32.7) | |||

| III | 118 (43.7) | 319 (40.7) | 0.111 | 299 (40.0) | 138 (45.1) | 0.199 | |

| Complications | No | 206 (76.3) | 608 (77.6) | 598 (79.9) | 216 (70.6) | ||

| Yes | 64 (23.7) | 176 (22.4) | 0.734 | 150 (20.1) | 90 (29.4) | 0.001 | |

| Chemotherapy | No | 124 (45.9) | 302 (38.5) | 316 (42.2) | 110 (35.9) | ||

| Yes | 146 (54.1) | 482 (61.5) | 0.039 | 432 (57.8) | 196 (64.1) | 0.068 | |

| Index year | 2006–2009 | 113 (41.9) | 329 (42.0) | 250 (33.4) | 192 (62.7) | ||

| 2010–2014 | 157 (58.1) | 455 (58.0) | >0.99 | 498 (66.6) | 114 (37.3) | <0.001 | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.8±0.2 | 0.9±0.4 | <0.001 | 0.7±0.2 | 1.1±0.5 | <0.001 | |

| SMI (cm2/m2) | 39.1±5.6 | 51.7±7.0 | <0.001 | 48.2±8.7 | 49.0±8.4 | 0.189 | |

| SMD (HU) | 41.0±8.7 | 42.8±8.4 | 0.004 | 42.6±8.3 | 41.5±8.9 | 0.054 |

Values are presented as number (%) or mean±standard deviation.

SMI = skeletal muscle index; BMI = body mass index; CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen; G1 = no sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; G2 = no sarcopenia with high serum creatinine levels; G3 = sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; MC = mucinous adenocarcinoma; SRC = signet-ring cell; LVI = lymphovascular invasion; SMD = skeletal muscle radiodensity; HU = Hounsfield unit.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with overall survival

| Variable | Categorization | Univariate analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Sex | Female | 1 | |

| Male | 1.205 (0.871–1.666) | 0.26 | |

| Age (yr) | <70 | 1 | |

| ≥70 | 2.592 (1.895–3.546) | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | No | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.041 (0.702–1.541) | 0.843 | |

| Hypertension | No | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.324 (0.968–1.811) | 0.078 | |

| Smoking | No | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.940 (0.668–1.323) | 0.725 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <25 | 1 | |

| ≥25 | 0.575 (0.390–0.848) | 0.005 | |

| CEA (ng/mL) | <5 | 1 | |

| ≥5 | 2.012 (1.456–2.781) | <0.001 | |

| Unknown | 1.044 (0.456–2.386) | 0.919 | |

| Tumor location | Colon | 1 | |

| Rectum | 0.913 (0.646–1.291) | 0.608 | |

| Complications | No | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.91 (1.372–2.658) | <0.001 | |

| Histologic grade | G1 & G2 | 1 | |

| G3 & MC & SRC | 2.114 (1.347–3.317) | 0.001 | |

| LVI | Absent | 1 | |

| Present | 2.197 (1.559–3.096) | <0.001 | |

| Unknown | 1.331 (0.791–2.237) | 0.281 | |

| Lymph nodes | <12 | 1 | |

| ≥12 | 0.657 (0.450–0.961) | 0.03 | |

| Stage | I | 1 | |

| II | 2.316 (1.287–4.169) | 0.005 | |

| III | 4.528 (2.630–7.795) | <0.001 | |

| Chemotherapy | No | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.859 (0.626–1.179) | 0.347 | |

| Index year | 2006–2009 | 1 | |

| 2010–2014 | 0.573 (0.419–0.785) | <0.001 | |

| SMI (cm2/m2) | Low | 1 | |

| High | 0.544 (0.393–0.752) | <0.001 | |

| SMD (HU) | Low | 1 | |

| High | 0.384 (0.281–0.525) | <0.001 | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | Low | 1 | |

| High | 2.086 (1.523–2.858) | <0.001 | |

| Combined groups | G1 | 1 | |

| G2 | 2.446 (1.650–3.628) | <0.001 | |

| G3 | 2.223 (1.453–3.401) | <0.001 | |

| G4 | 3.702 (2.223–6.163) | <0.001 | |

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; BMI = body mass index; CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen; G1 = no sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; G2 = no sarcopenia with high serum creatinine levels; G3 = sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; MC = mucinous adenocarcinoma; SRC = signet-ring cell; LVI = lymphovascular invasion; SMI = skeletal muscle index; SMD = skeletal muscle radiodensity; HU = Hounsfield unit; G4 = sarcopenia with high serum creatinine level.

Multivariable analysis of factors associated with overall survival

| Variable | Categorization | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | <70 | 1 | |

| ≥70 | 1.863 (1.314–2.641) | <0.001 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <25 | 1 | |

| ≥25 | 0.643 (0.431–0.958) | 0.030 | |

| CEA (ng/mL) | <5 | 1 | |

| ≥5 | 1.468 (1.048–2.056) | 0.025 | |

| Unknown | 1.824 (0.787–4.227) | 0.160 | |

| Complications | No | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.498 (1.055–2.127) | 0.023 | |

| Histologic grade | G1 & G2 | 1 | |

| G3 & MC & SRC | 1.514 (0.951–2.412) | 0.080 | |

| Lymph nodes | <12 | 1 | |

| ≥12 | 0.511 (0.337–0.773) | 0.001 | |

| Stage | I | 1 | |

| II | 1.606 (0.851–3.028) | 0.143 | |

| III | 3.558 (2.000–6.328) | <0.001 | |

| Index year | 2006–2009 | 1 | |

| 2010–2014 | 0.707 (0.505–0.990) | 0.043 | |

| SMD (HU) | Low | 1 | |

| High | 0.615 (0.435–0.870) | 0.006 | |

| Combined groups | G1 | 1 | |

| G2 | 1.676 (1.110–2.529) | 0.013 | |

| G3 | 1.916 (1.249–2.938) | 0.002 | |

| G4 | 2.172 (1.279–3.687) | 0.004 |

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; BMI = body mass index; CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen; G1 = no sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; G2 = no sarcopenia with high serum creatinine levels; G3 = sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; MC = mucinous adenocarcinoma; SRC = signet-ring cell; SMD = skeletal muscle radiodensity; HU = Hounsfield unit; G4 = sarcopenia with high serum creatinine level.

Comparison of C-index between combined group and skeletal muscle index or serum creatinine alone

| Included variable | Combined group | SMI | Combined group | Creatinine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-index (95% CI) (bootstrapped) | 0.626 (0.587–0.666) | 0.564 (0.524–0.602) | 0.626 (0.587–0.666) | 0.583 (0.544–0.623) |

| Estimated difference | 0.062 (0.031–0.103) | 0.043 (0.017–0.081) | ||

C-index = Harrell’s concordance index; SMI = skeletal muscle index; CI = confidence interval.

Values are presented as number (%) or mean±standard deviation. SMI = skeletal muscle index; BMI = body mass index; CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen; G1 = no sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; G2 = no sarcopenia with high serum creatinine levels; G3 = sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; MC = mucinous adenocarcinoma; SRC = signet-ring cell; LVI = lymphovascular invasion; SMD = skeletal muscle radiodensity; HU = Hounsfield unit.

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; BMI = body mass index; CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen; G1 = no sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; G2 = no sarcopenia with high serum creatinine levels; G3 = sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; MC = mucinous adenocarcinoma; SRC = signet-ring cell; LVI = lymphovascular invasion; SMI = skeletal muscle index; SMD = skeletal muscle radiodensity; HU = Hounsfield unit; G4 = sarcopenia with high serum creatinine level.

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; BMI = body mass index; CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen; G1 = no sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; G2 = no sarcopenia with high serum creatinine levels; G3 = sarcopenia with low serum creatinine level; MC = mucinous adenocarcinoma; SRC = signet-ring cell; SMD = skeletal muscle radiodensity; HU = Hounsfield unit; G4 = sarcopenia with high serum creatinine level.

C-index = Harrell’s concordance index; SMI = skeletal muscle index; CI = confidence interval.

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite