Abstract

-

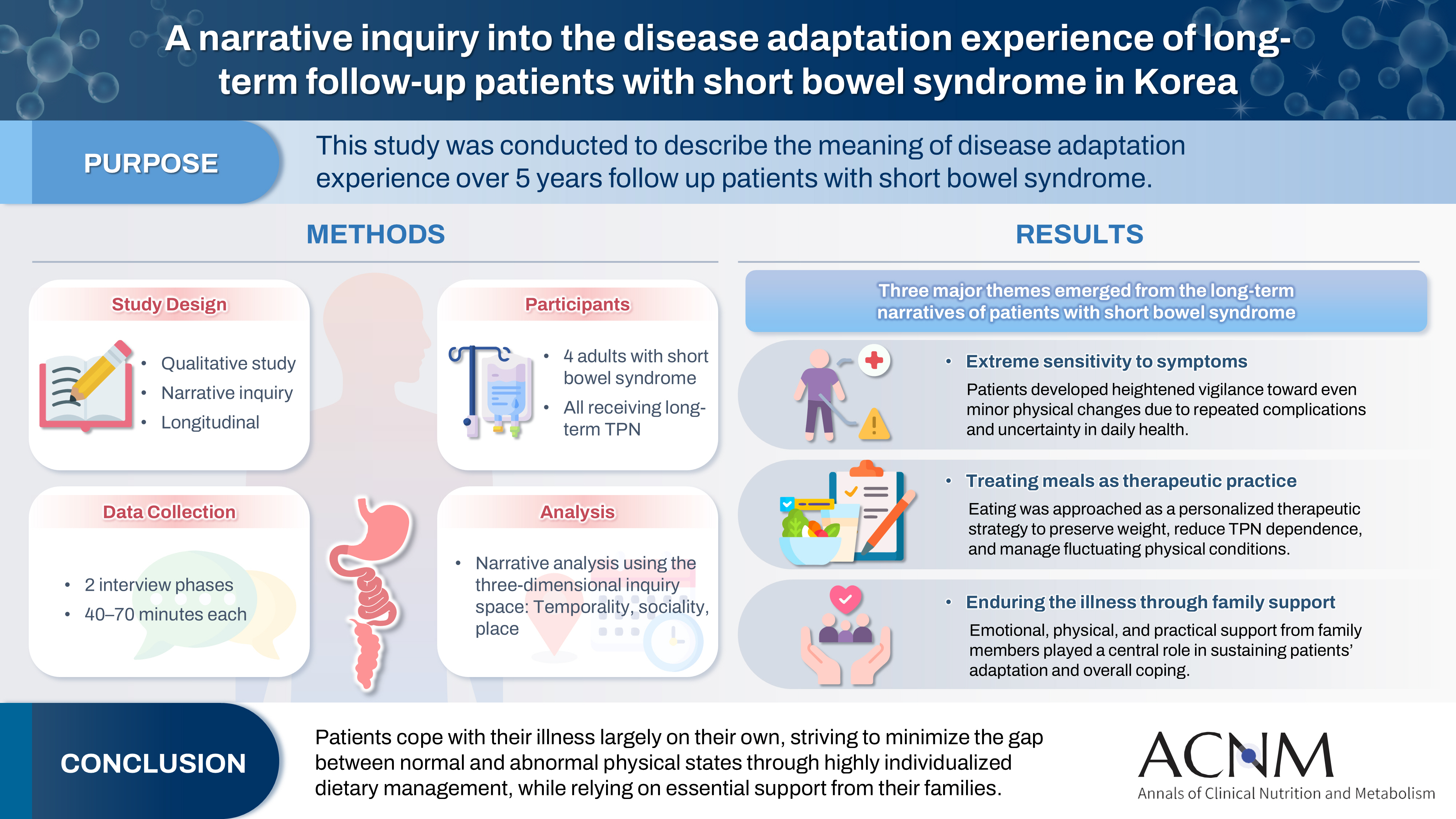

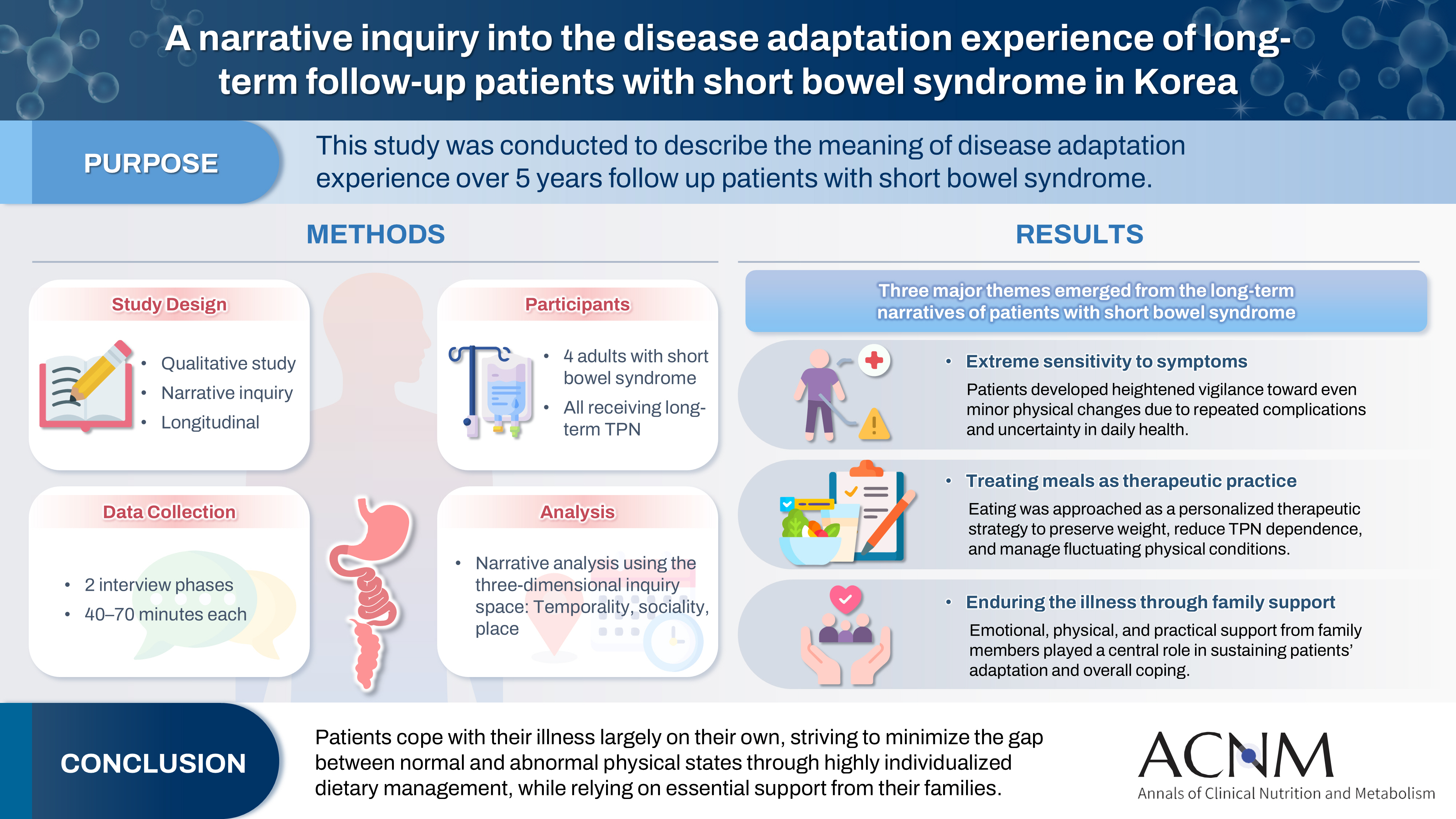

Purpose

This study was conducted to describe the meaning of disease adaptation experience over a 5-year long-term follow-up of patients with short bowel syndrome.

-

Methods

Four patients were recruited from a tertiary hospital in Korea. This study was conducted through first and second interviews from January 2019 to July 2022. The transcribed data were analyzed using narrative methods.

-

Results

The mean age of the participants was 64 years, and the mean treatment period after small bowel resection was 100 months. The participants lost a mean of 19.3 kg body weight and all were receiving home total parenteral nutrition 2–7 days a week. The meaning of the experience of adapting to the disease for patients was found to be “extremely sensitive to the symptoms,” “considering eating food as another effective treatment method,” and “enduring the disease through family affection.”

-

Conclusion

Patients are struggling alone to cope with physical symptoms and adapt to their disease. For this, they are doing their best to narrow the gap between normal and abnormal physical conditions by thoroughly implementing diet therapy according to their physical characteristics. This entire process is supported by their families.

-

Keywords: Adaptation, physiological; Intestinal failure; Qualitative research; Short bowel syndrome; Therapy

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Short bowel syndrome (SBS) refers to a group of metabolic disorders caused by congenital or acquired shortening of the small intestine, resulting in impaired digestion and nutrient absorption [

1]. In essence, the shorter the remaining functional small intestine, or the longer the segment rendered nonfunctional, the less surface area and time available for nutrient absorption. This accelerates the transit of food, increasing the risk of malabsorption and a range of associated symptoms [

1-

3]. Removal of the distal ileum and the ileocecal (IC) valve further causes rapid intestinal transit, hypersecretion, and gastric dumping due to the loss of hormonal feedback mechanisms. Additionally, disruption of intestinal motility and IC valve function often leads to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), which exacerbates malabsorption and contributes to fat malabsorption. SIBO is commonly associated with abdominal distension, abdominal pain, and diarrhea [

4,

5].

The prevalence of SBS remains unclear; however, data from home intravenous nutrition programs estimate it at 5–80 per million in the United States and Europe, and approximately 3.5 per million in Korea [

6-

10]. SBS is thus among the rarest diseases both in Korea and globally. Notably, appropriate diagnostic codes for intestinal failure and SBS were only incorporated into the ICD-11 in 2022. Regarding economic burden, direct medical costs for SBS average $44,500 in the first year following small bowel resection. Although these costs decline over time, they remain substantial—averaging at least $6,800 annually 5 years postoperatively [

1,

10]. These data underscore SBS as a lifelong condition with significant, persistent disease burden.

Meanwhile, dehydration is common in SBS due to greater secretion in the upper small intestine compared to absorption in the lower portion. In response, participants often increase water intake, which paradoxically worsens dehydration and perpetuates a vicious cycle. Bowel adaptation typically occurs over 6 months to 2 years, depending on the individual [

11,

12]. If symptoms do not respond to medical management and bowel adaptation is not achieved within the adaptation period, bowel transplantation may be considered, particularly in cases of life-threatening complications, severe dehydration, or recurrent central line–related issues [

13]. For patients ineligible for intestinal transplantation, home intravenous nutrition becomes the primary nutritional strategy to compensate for intestinal function loss. In the United States, Europe, and other countries, home total parenteral nutrition (TPN) has demonstrated cost-effectiveness as part of bowel rehabilitation, with structured guidelines and educational support. However, in Korea, standardized protocols for home intravenous nutrition education remain lacking [

3,

7]. Home intravenous nutrition requires close attention to individualized nutritional and fluid–electrolyte needs, with rapid adjustments based on minor clinical changes. It also demands careful management to avoid under- or over-nutrition. Most individuals with SBS, along with their primary caregivers, manage their TPN and catheters—critical lifelines—with a persistent sense of urgency and anxiety. Previous research on SBS has largely focused on nutrient deficiencies associated with intravenous nutrition [

14-

16], case reports of specific instances [

17,

18], and studies examining pharmaceutical interventions or enteral rehabilitation programs in pediatric populations [

19-

23]. However, these investigations are predominantly limited to short-term analyses with small sample sizes. To date, only three qualitative studies have explored the lived experiences of individuals with SBS, highlighting a need for more comprehensive, patient-centered research [

23-

25].

Narrative research, a qualitative methodology, centers on each participant’s life story and seeks to understand the individual's experience across past, present, and future to derive meaning and establish new values and directions [

26]. In this study, we employed a narrative research approach to examine the lived experiences of patients with SBS as they adapt to their disease. The goal was to reconstruct the meaning embedded in their narratives to better address the challenges encountered during the adaptation process and to offer insights that can inform long-term clinical management through empirically grounded evidence.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. 1890/002-001). Prior to data collection, participants were informed of the study’s purpose and procedures, including audio recording of interviews, and provided written informed consent. Participants were assured of their rights, including the option to pause or terminate the interview if they experienced physical or psychological discomfort and the ability to withdraw from the study at any time without consequence.

Study design

This qualitative study employed Clandinin and Connelly’s narrative inquiry method to explore and describe the lived experiences of individuals with SBS as they adjusted to their illness [

26]. Given that SBS is characterized by fluctuating symptoms and ongoing adaptation, a longitudinal narrative design was incorporated to capture the evolving nature of participants’ interpretations and coping processes. Two interview phases were used to enhance narrative depth and ensure completeness of participants’ accounts within their evolving illness trajectories.

Participants were individuals aged ≥19 years diagnosed with SBS at a university hospital in Seoul, Korea. Purposive sampling was used for efficient participant selection. Initially, six participants were recruited; however, two withdrew after the initial interview for personal reasons, leaving a final sample of four participants. Narrative inquiry focuses on individual life experiences and the meanings ascribed to them, and it may include more than one participant [

27]. The mean age of participants was 64 years. They had been diagnosed with SBS following a mean of three bowel resections. The mean duration since the last bowel resection was 8 years and 4 months. All participants had a remaining bowel length of <100 cm and had lost a mean of 19.3 kg since diagnosis. All were receiving nutritional support via TPN. On mean, participants received TPN 5 days per week and infused approximately 915 mL of fluid per day (

Table 1).

The researchers had 18 and 23 years of clinical experience, respectively, at a tertiary hospital in Seoul and had served on the nutrition support team (NST) for approximately 10 years, caring for patients with SBS. They also participated in periodic outpatient multidisciplinary consultations post-discharge, allowing for the development of close, ongoing relationships with patients. Furthermore, both researchers completed at least two semesters of qualitative research methodology during their graduate nursing education and had experience conducting qualitative studies using diverse approaches.

Interview and procedure

Data collection occurred in two phases, from January 2019 to July 2022. The first phase spanned January to August 2019. Each interview lasted 40–70 minutes (mean: 50 minutes), with seven to eight sessions conducted per participant. Interviews were one-on-one between the researcher and participant; however, for two participants who experienced physical limitations, a caregiver was present with the participant’s consent.

The interviews were held in a quiet hospital conference room. Interviews began with unstructured questions and transitioned to semi-structured ones. Key questions included: “What does it mean to live with SBS?,” “How does living with SBS change your life?,” “What are some of the most challenging experiences you've had?,” “What gives you the strength to cope with your illness?,” and “What are some of the things you’ve learned to live with?”

The second phase occurred from September 2019 to July 2022. During informed consent, participants were informed that the number of interviews could vary based on study needs. In this phase, participants completed seven to eight interviews, each lasting approximately 30 minutes. Follow-up questions addressed missing details, clarified emerging themes, and explored additional researcher concerns. Interviewers also observed participants’ facial expressions and voice intensity to assess reactions.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Clandinin and Connelly’s narrative inquiry framework, guided by the three-dimensional inquiry space of temporality, sociality, and place [

26]. Analysis began with repeated readings of each transcript, after which we constructed individual narrative accounts by organizing participants’ experiences across past events, present adaptation processes, and anticipated futures.

We then examined sociality by identifying both personal conditions (e.g., emotions, bodily reactions, coping strategies) and social conditions (e.g., family dynamics, caregiving roles, interactions with healthcare professionals). Attention to place allowed us to consider how settings—such as the hospital or home—shaped experiences and meanings.

In the next stage, reconstructed stories were compared across participants to identify recurring patterns, contrasts, and temporal flows of adaptation (e.g., early crisis, stabilization, long-term management). Throughout the process, we moved iteratively between transcripts, narrative accounts, and emerging interpretations to ensure that meanings remained grounded in participants’ lived contexts. Themes were finalized by mapping how the three dimensions converged within and across stories, clarifying how participants’ experiences gained meaning over time and within relational and situational contexts.

Rather than comparing the two interview phases as separate datasets, participants’ experiences were interpreted as a continuous illness trajectory. Accordingly, temporal shifts were embedded within the holistic storyline, consistent with narrative inquiry principles.

Results

The qualitative analysis conducted to gain an understanding of the experience of SBS patients, yielded themes and contents (

Table 2). Additional information is provided in the

Supplement 1.

Participant A story

1) Story 1. The life you obsessively record to survive

Participant A, a businessman in the construction industry, had developed a lifelong habit of meticulous recordkeeping. Following his diagnosis with SBS, he continued this practice, maintaining computerized records of every meal—including type, calories, and ingredients—as well as detailed logs of bowel and bladder movements. He reviewed these data daily to objectively assess his condition and consulted with the NST when necessary.

2) Story 2. Commitment to disease-related information

SBS is among the rarest diseases, making information scarce. Unlike cancer, SBS lacks both peer networks and readily available, practical guidance. Determined to understand how to manage life with SBS, he turned to academic journals. He sought evidence on how healthcare professionals treat patients with SBS, what dietary restrictions are recommended, and which aspects of daily living require caution—all to construct an informed lifestyle plan.

3) Story 3. Hope with absolute trust in medical staff

For participant A, healthcare providers were akin to “the captain of a ship in the middle of a stormy sea.” Most of his acquaintances who were living with other illnesses utilized folk remedies alongside hospital-based care, often recommending herbal medicines and nutritional supplements, and sending gifts. However, he strictly adhered to the medical team’s directives, placing unwavering trust in them.

Participant B story

1) Story 1. Appreciation only found by comparing to other patients

Participant B reflected on her father's condition: bedridden in a nursing home with a tracheostomy tube due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. His life was severely restricted. In contrast, Participant B could choose her meals and walk independently. Despite requiring daily TPN to survive and facing ongoing risks of TPN, she considered her life more autonomous than that of a bedridden patient.

2) Story 2. Reclaiming your life through work

Participant B had worked as a dental hygienist since age 24. Throughout her career, she experienced multiple small bowel obstructions and ruptures requiring emergency surgery. Despite these events, she tried to maintain her job. After adjusting to TPN, she prayed to switch to cyclic TPN. Although she could not return to full-time work, having a job restored her sense of autonomy and humanity beyond being a patient with illness.

Participant C story

1) Story 1. Appetite control learned through experience

Participant C had a voracious appetite even prior to his diagnosis with SBS. He described eating as his primary joy in life. However, following an intestinal perforation, five episodes of intestinal adhesions, and a small bowel resection due to obstruction, he was unable to eat by mouth for 1.5 years and depended entirely on TPN. Once he regained sufficient physical strength to eat orally, he consumed food uncontrollably, fearing he might soon lose the ability to eat again. He experienced severe complications from this behavior—once losing 7 kg overnight due to diarrhea and another time suffering severe abdominal pain and vomiting, which resulted in a 10-month hospitalization and several intensive care unit admissions.

2) Story 2. Total dependence on wife

Participant C explained that following five small bowel resections, he became unable to perform daily tasks independently because of severe, unrelenting pain. After 9 years of hospitalizations, repeated procedures, and surgeries, he began to rely entirely on his wife, gradually delegating all household decisions to her. Although healthcare providers advised him to eat, exercise, and rest within limits, he reported being unable to assess what constituted overexertion and routinely consulted his wife for guidance.

Participant D story

1) Story 1. Voluntary isolation from relationships

Participant D, previously an extroverted and socially active individual, had organized regular couple’s gatherings with friends for over a decade. After being diagnosed with SBS, however, he began to avoid social interactions, finding it emotionally difficult to watch others eat freely while he was restricted. He also struggled with the contrast between his current state and the continued vibrant social lives of his friends.

2) Story 2. Forcing yourself to eat a given amount of food per day

Participant D underwent three small bowel resections and subsequently required TPN and intravenous fluids for approximately 7 months, due to persistent severe nausea and vomiting. Participant D was required to consume approximately 2,800 kcal and 100 g of protein per day—excluding calories from TPN, which were poorly absorbed due to his shortened bowel. Although he was motivated to eat more, his gastric capacity remained limited due to prolonged disuse. To meet his nutritional goals, he set alarms on his phone and forced himself to eat small amounts at regular intervals, treating the process like a mandatory task.

Implications of disease adaptation in patients with SBS

Extreme sensitivity to symptoms

Living with SBS has made participants highly sensitive and reactive to even minor symptoms. This heightened vigilance stems from repeated emergency room visits and intensive care admissions for complications such as catheter infections, sepsis, urinary tract stones, kidney stones, bloody stools, and impaired liver function. Consequently, participants exhibited extreme anxiety in response to any unusual symptoms and took immediate action to manage them. For instance, they decreased fluid intake when experiencing loose or frequent stools, increased food and fluid intake when noticing weight loss or excessive sweating, and closely monitored even minor physical discomfort. They paid attention to digestion time, the smell of flatulence, and the frequency of burping to assess their condition.

Treat meals as another form of therapy

Participants, who had minimal remaining small intestine had lost a mean of 19.3 kg since their SBS diagnosis. For them, eating was not simply for sustenance; it was a therapeutic strategy to minimize weight loss and reduce dependence on TPN, enabling a semblance of daily routine. Due to reduced gastric capacity, participants replaced the conventional three-meal structure with six smaller meals daily. They continually sought strategies to increase oral calorie and nutrient intake through personal research and experimentation.

Drawing strength from family as a source of hope

For one participant who had lived with the condition for nearly 9 years, the love and support of family were central to enduring the disease and sustaining a sense of hope. Family members were often the only individuals capable of offering meaningful emotional support, and their understanding and encouragement provided essential physical, material, and emotional stability. For patients with SBS—whose condition is both uncommon and often misunderstood—this unwavering familial support became a crucial source of strength and hope.

Discussion

SBS is an extremely rare condition with limited epidemiological data, as its low prevalence hinders accurate determination of incidence. This study is significant in that it offers an in-depth understanding of the lived long-term experiences of individuals with SBS. Most prior research has focused primarily on the disease itself, rather than on the day-to-day lives of those affected. Furthermore, few qualitative studies have conducted in-depth interviews with patients with SBS, and none have examined their long-term adaptation to the illness. By focusing on extended illness trajectories rather than short-term episodes, this study provides meaningful insights into both the illness experience and the long-term adjustment process. In a systematic review by Rosland et al. [

28], the participants’ ability to maintain intestinal adaptation for nearly 8 years following diagnosis appeared to be closely linked to their sensitivity to even minor symptoms. This heightened symptom awareness contributed to successful adaptation but was also rooted in fear and anxiety regarding potential complications. Winkler et al. [

29] analyzed data from 1,251 patients enrolled in the Sustain Registry across 29 U.S. sites from August 2011 to February 2014 and found SBS to be the most common indication for home parenteral nutrition (HPN). Although no studies have specifically reported the incidence of HPN-related complications among patients with SBS, the incidence of catheter-related infections during long-term HPN at 0.64–0.66 per 1,000 catheter days [

30,

31]. While this rate may appear low, it likely underrepresents the actual prevalence of catheter infections in clinical settings. Patients with SBS who are on long-term HPN and not under continuous medical supervision remain highly vulnerable to these complications. Therefore, ongoing education and consistent monitoring of catheter and intravenous nutrient management are essential for patients with SBS and their caregivers, particularly those requiring HPN for ≥2 years to facilitate intestinal adaptation. The study revealed that patients with SBS often lacked accessible support when experiencing unfamiliar symptoms or pain. In South Korea, only a limited number of large medical institutions and regional hub hospitals provide coordinated post-discharge home care through home nursing teams. Even in these settings, home visits are typically restricted to once weekly after the first week post-discharge. Consequently, patients with SBS who require prolonged HPN often lack a continuous support system bridging hospital and home, leaving them without reliable assistance when complications occur. As a result, participants reported financial strain related to emergency department visits and sought to manage symptoms at home whenever possible, either through self-care or by consulting a home health nurse. However, this often led to delays in addressing severe complications—such as systemic infections or catheter-related issues—that required urgent specialist intervention, sometimes resulting in life-threatening outcomes. In contrast, the United States has implemented center-based intestinal failure programs [

31]. These programs utilize multidisciplinary teams—comprising physicians, pharmacists, dietitians, and nurses—to provide individualized HPN preparation and management. This model enables patients with intestinal failure to practice HPN safely and flexibly in out-of-hospital settings [

31]. Previous qualitative studies reported that patients with SBS and their families identified the absence of parenteral nutrition at night as a factor positively influencing quality of life [

32]. Accordingly, the principal aim of intestinal rehabilitation for SBS is to improve quality of life by addressing malnutrition and enabling patients to sustain themselves through oral feeding without intravenous nutritional support. Furthermore, 90% of patients with SBS and intestinal failure receiving HPN were cared for by family members, 61% of whom were identified as spouses or partners [

32], and 77% of caregivers provided care daily, 7 days a week. Their responsibilities included housework, grocery shopping, companionship, emotional support, transportation to medical appointments, meal preparation, and HPN administration [

7,

32]. As the primary providers of direct care, family members represent a vital support system offering physical and emotional assistance to patients living with a severe chronic condition such as SBS. However, alongside the recognized burdens and fatigue experienced by family caregivers—including challenges with time management and professional responsibilities—depression among caregivers has been identified as the strongest predictor of poor illness adjustment in families managing chronic disease [

33]. Establishing a robust care support framework within the healthcare and social welfare systems is an urgent priority to mitigate the burden on families managing long-term, severe conditions such as SBS.

Beyond the need for multidisciplinary management, this study shows that patients’ adjustment to SBS involves ongoing meaning-making shaped through relationships with family and healthcare providers. Thus, clinical practice would benefit from a narrative-centered approach that emphasizes listening to patients’ stories and supporting them in reconstructing their illness narratives alongside standardized biomedical care.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the findings are based on a small sample from a single tertiary hospital, which may limit their broader transferability. Second, although the long-term follow-up design strengthened the depth of understanding, the narratives relied partly on participants’ retrospective accounts and may be influenced by recall bias. Finally, because the study examined only patients’ perspectives, the absence of caregiver and healthcare provider viewpoints may constrain the comprehensiveness of the findings. Future studies incorporating larger, multicenter samples and multiple stakeholder perspectives are warranted to enhance the applicability and robustness of the evidence.

Conclusions

This study aimed to describe and interpret the illness adjustment experiences of four participants with SBS using a narrative inquiry approach. For individuals with SBS, the process of adjustment involved coping with symptoms with heightened sensitivity, viewing food intake as a form of therapy, and enduring the illness through familial support. The findings indicate that participants with SBS often face the burden of self-managing their condition in isolation, relying primarily on family. They independently determine their dietary and exercise routines and respond sensitively to physical symptoms to maintain a state of relative comfort aligned with their physical conditions.

Based on the study findings, the following recommendations are proposed. First, multidisciplinary and individualized interventions are needed to address the comprehensive physical, psychological, and socioeconomic challenges faced by individuals with SBS during the adjustment process. Second, it is essential to develop clinical guidelines that provide accurate information about SBS and facilitate inter-institutional resource sharing to promote standardized treatment and management for this rare and incurable condition.

Authors’ contribution

Eun-Mi Seol and Eunjung Kim contributed equally to this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

None.

Data availability

Contact the corresponding author for research data availability.

Acknowledgments

None.

Supplementary materials

Table 1.Participant’s characteristics

|

Participant |

Sex |

Age (yr) |

Underlying disease |

No. of bowel resection |

Period after last bowel resection |

Remnant bowel |

Body weight loss (kg) |

Days of TPN (wk) |

Fluid volume (mL/day) |

|

A |

M |

68 |

Gastric cancer |

3 |

9 yr |

80 cm with IC valve |

25 |

2 |

App. 210 |

|

B |

F |

45 |

Colon cancer |

3 |

6 yr 10 mo |

60 cm with IC valve |

16 |

7 (cyclic TPN 10 hr off) |

App. 1,400 |

|

C |

M |

69 |

Gastric cancer |

5 |

8 yr 9 mo |

70 cm with IC valve |

19 |

7 |

App. 1,400 |

|

D |

M |

72 |

Gastric cancer |

3 |

8 yr 8 mo |

50 cm with IC valve |

17 |

3 |

App. 650 |

Table 2.

|

Participant |

Theme |

Contents |

Overall theme |

|

A |

(1) The life you obsessively record to survive |

“I have a notebook and I write down my weight every day... When I was in the hospital, I weighed myself at 6:00 a.m. before breakfast, so I do the same at home. (interruption) I do not just have one data sheet. I have many—one for each day, each month. Everything is organized by date, month, year. It is all saved on CDs and an external hard drive—over two terabytes of organized data.” |

Extreme sensitivity to symptoms |

|

(2) Commitment to disease-related information |

“I was really stressful because there are limited resources for SBS. With cancer, if you search for resources, there is information. But for small bowel, there is nothing...” |

Extreme sensitivity to symptoms |

|

(3) Hope with absolute trust in medical staff |

“Code... I must now... match the code between the medical staff and me. (interruption) I am just going to focus on the doctor, the nurse, the nutritionist, and what they are saying, and I am not going to trust anything else.” |

Extreme sensitivity to symptoms |

|

B |

(1) Appreciation only found by comparing to other patients |

“My dad has been in a nursing home for over 2 years with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He has not set foot on the ground once, and he is older now, so he cannot return home. I just think my illness is better than others. I am doing better among people with illnesses...” |

Treat meals as another form of therapy |

|

(2) Reclaiming your life through work |

“My job is my reason for living. I was crying in the hospital because I could not work; it was unbearable. So I need to go back—I feel brighter and more energetic when I work.” |

Treat meals as another form of therapy |

|

C |

(1) Appetite control learned through experience |

“I just ate it all. Suddenly I felt blocked, then vomited, and had diarrhea four or five times. Eventually, I had a rupture. (interruption) I could not eat well for a while, then I ate again, thinking I could handle it. I should have stopped myself.” |

Treat meals as another form of therapy |

|

2) Total dependence on wife |

“I have been very sick since I was admitted to the hospital, and if it were not for my wife—my caregiver—I believe I would already be dead. (interruption) I believe I am alive today because of my wife.” |

Endure with family love |

|

D |

(1) Voluntary isolation from relationships |

“I feel more at ease at home with my family, where I do not have to resist the urge to eat or explain myself. I simply do not go. I feel better that way.” |

Endure with family love |

|

(2) Forcing yourself to eat a given amount of food per day |

“To meet my nutritional goals, I set alarms on my phone and forced myself to eat small amounts at regular intervals, treating the process like a mandatory task.” |

Endure with family love |

References

- 1. Winkler M, Tappenden K. Epidemiology, survival, costs, and quality of life in adults with short bowel syndrome. Nutr Clin Pract 2023;38 Suppl 1:S17-26. ArticlePubMed

- 2. Christian VJ, Van Hoorn M, Walia CLS, Silverman A, Goday PS. Pediatric feeding disorder in children with short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2021;72:442-5. ArticlePubMed

- 3. Pironi L, Cuerda C, Jeppesen PB, Joly F, Jonkers C, Krznaric Z, et al. ESPEN guideline on chronic intestinal failure in adults: update 2023. Clin Nutr 2023;42:1940-2021. ArticlePubMed

- 4. Dibaise JK, Young RJ, Vanderhoof JA. Enteric microbial flora, bacterial overgrowth, and short-bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:11-20. ArticlePubMed

- 5. Kelly DG, Tappenden KA, Winkler MF. Short bowel syndrome: highlights of patient management, quality of life, and survival. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2014;38:427-37. ArticlePubMed

- 6. Brandt CF, Hvistendahl M, Naimi RM, Tribler S, Staun M, Brobech P, et al. Home parenteral nutrition in adult patients with chronic intestinal failure: the evolution over 4 decades in a tertiary referral center. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2017;41:1178-87. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 7. Pironi L, Boeykens K, Bozzetti F, Joly F, Klek S, Lal S, et al. ESPEN guideline on home parenteral nutrition. Clin Nutr 2020;39:1645-66. ArticlePubMed

- 8. Mundi MS, Mercer DF, Iyer K, Pfeffer D, Zimmermann LB, Berner-Hansen M, et al. Characteristics of chronic intestinal failure in the USA based on analysis of claims data. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2022;46:1614-22. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 9. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Prevalence and disease burden of patients with short bowel syndrome [Internet]. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service; 2018. [cited 2024 Sep 10]. Available from: https://repository.hira.or.kr/handle/2019.oak/1452

- 10. Braszczynska-Sochacka J, Kunecki M, Sochacki J, Bak-Romaniszyn L. Short bowel syndrome: experience from a home parenteral nutrition centre. Arch Med Sci 2021;17:1140-4. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 11. Nightingale JM, Lennard-Jones JE, Walker ER, Farthing MJ. Oral salt supplements to compensate for jejunostomy losses: comparison of sodium chloride capsules, glucose electrolyte solution, and glucose polymer electrolyte solution. Gut 1992;33:759-61. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. Jeppesen PB. Clinical significance of GLP-2 in short-bowel syndrome. J Nutr 2003;133:3721-4. ArticlePubMed

- 13. Billiauws L, Maggiori L, Joly F, Panis Y. Medical and surgical management of short bowel syndrome. J Visc Surg 2018;155:283-91. ArticlePubMed

- 14. Braga CB, Vannucchi H, Freire CM, Marchini JS, Jordao AA, da Cunha SF, et al. Serum vitamins in adult patients with short bowel syndrome receiving intermittent parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2011;35:493-8. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 15. Herath T, Kulatunga A. Delayed presentation of short bowel syndrome complicated with severe degree of nutritional deficiencies, nephrocalcinosis and distal renal tubular acidosis. J Gastrointest Dig Syst 2017;7:484.Article

- 16. An SH, Lee S, Park HJ, Seo JM. Vitamin D deficiency in short bowel syndrome patients on long-term parenteral nutrition support. J Clin Nutr 2021;13:12-6. Article

- 17. Morotti F, Terruzzi J, Cavalleri L, Betalli P, D'Antiga L, Norsa L, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency presenting as intestinal pseudo-obstruction in short bowel syndrome: a case report. Nutrition 2023;106:111895.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Dixit D, Rodriguez VI, Ruiz NC, Kamel AY. Short Bowel Syndrome: a case study of multiple micronutrient deficiencies and high ileostomy output. Ann Clin Case Rep 2023;8:2425.

- 19. Merritt RJ, Cohran V, Raphael BP, Sentongo T, Volpert D, Warner BW, et al. Intestinal rehabilitation programs in the management of pediatric intestinal failure and short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017;65:588-96. ArticlePubMed

- 20. Carter BA, Cohran VC, Cole CR, Corkins MR, Dimmitt RA, Duggan C, et al. Outcomes from a 12-week, open-label, multicenter clinical trial of teduglutide in pediatric short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr 2017;181:102-11.e5. ArticlePubMed

- 21. Kocoshis SA, Merritt RJ, Hill S, Protheroe S, Carter BA, Horslen S, et al. Safety and efficacy of teduglutide in pediatric patients with intestinal failure due to short bowel syndrome: a 24-week, phase III study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2020;44:621-31. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 22. Khalil BA, Ba'ath ME, Aziz A, Forsythe L, Gozzini S, Murphy F, et al. Intestinal rehabilitation and bowel reconstructive surgery: improved outcomes in children with short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012;54:505-9. ArticlePubMed

- 23. Sowerbutts AM, Panter C, Dickie G, Bennett B, Ablett J, Burden S, et al. Short bowel syndrome and the impact on patients and their families: a qualitative study. J Hum Nutr Diet 2020;33:767-74. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 24. Seol EM, Kim E, Suh E. Illness experience of patients with short bowel syndrome. J Assoc Quali Res 2019;4:1-10. Article

- 25. Pederiva F, Khalil B, Morabito A, Wood SJ. Impact of short bowel syndrome on quality of life and family: the patient's perspective. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2019;29:196-202. ArticlePubMed

- 26. Connelly FM, Clandinin DJ. Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educ Res 1990;19:2-14. ArticlePDF

- 27. Lewis S. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Health Promot Pract 2015;16:473-5. ArticlePDF

- 28. Rosland AM, Heisler M, Piette JD. The impact of family behaviors and communication patterns on chronic illness outcomes: a systematic review. J Behav Med 2012;35:221-39. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 29. Winkler MF, DiMaria-Ghalili RA, Guenter P, Resnick HE, Robinson L, Lyman B, et al. Characteristics of a cohort of home parenteral nutrition patients at the time of enrollment in the Sustain registry. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2016;40:1140-9. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 30. Mundi MS, Mohamed Elfadil O, Hurt RT, Bonnes S, Salonen BR. Management of long-term home parenteral nutrition: historical perspective, common complications, and patient education and training. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2023;47 Suppl 1:S24-34. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 31. Bluthner E, Bednarsch J, Stockmann M, Karber M, Pevny S, Maasberg S, et al. Determinants of quality of life in patients with intestinal failure receiving long-term parenteral nutrition using the SF-36 questionnaire: a German single-center prospective observational study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2020;44:291-300. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 32. Jeppesen PB, Shahraz S, Hopkins T, Worsfold A, Genestin E. Impact of intestinal failure and parenteral support on adult patients with short-bowel syndrome: a multinational, noninterventional, cross-sectional survey. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2022;46:1650-9. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 33. Whitehead L, Jacob E, Towell A, Abu-Qamar M, Cole-Heath A. The role of the family in supporting the self-management of chronic conditions: a qualitative systematic review. J Clin Nurs 2018;27:22-30. ArticlePubMedPDF

, Eunjung Kim2

, Eunjung Kim2

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN

Cite

Cite