Abstract

-

Purpose

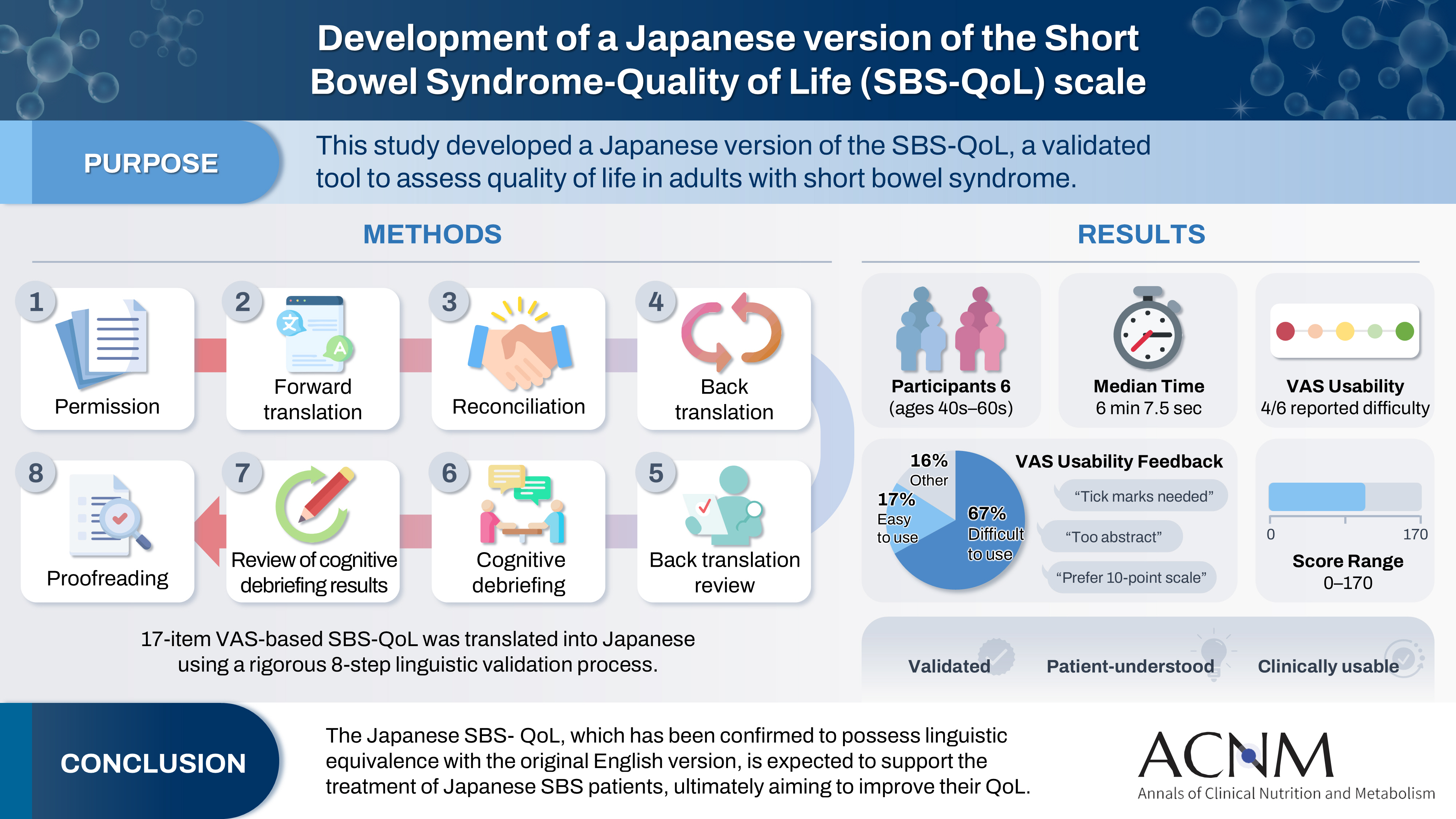

The Short Bowel Syndrome‐Quality of Life (SBS‐QoL) scale is a reliable and sensitive instrument developed to measure and evaluate the quality of life (QoL) in adult patients with short bowel syndrome (SBS). In Japan, increasing attention has been given to the assessment of QoL in patients with SBS; however, no Japanese‐language SBS‐specific scale is currently available. This study aimed to develop a Japanese version of the SBS‐QoL based on the original English version.

-

Methods

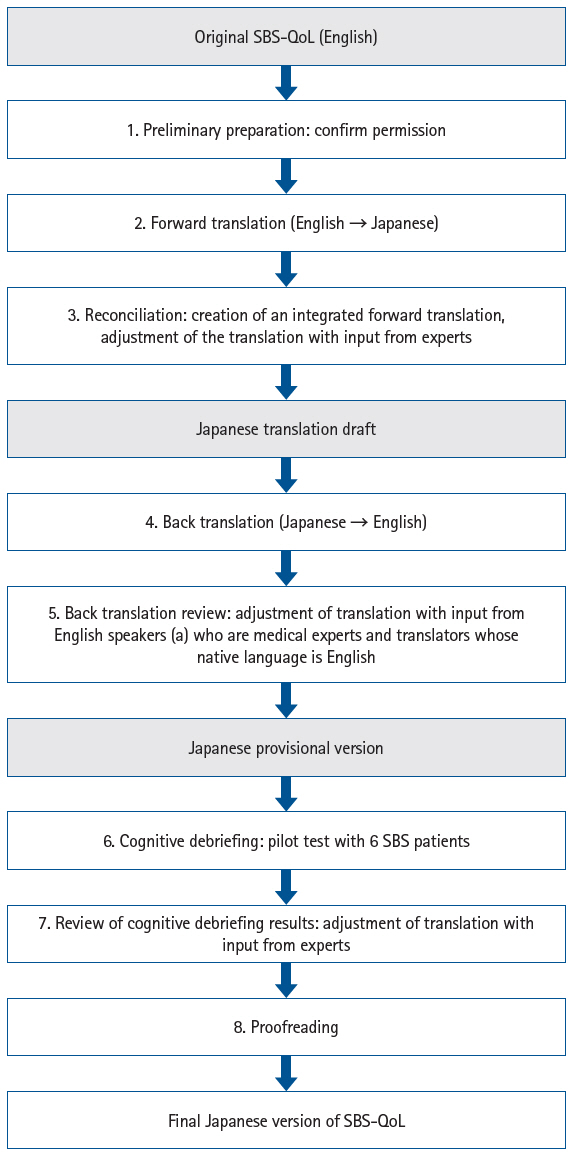

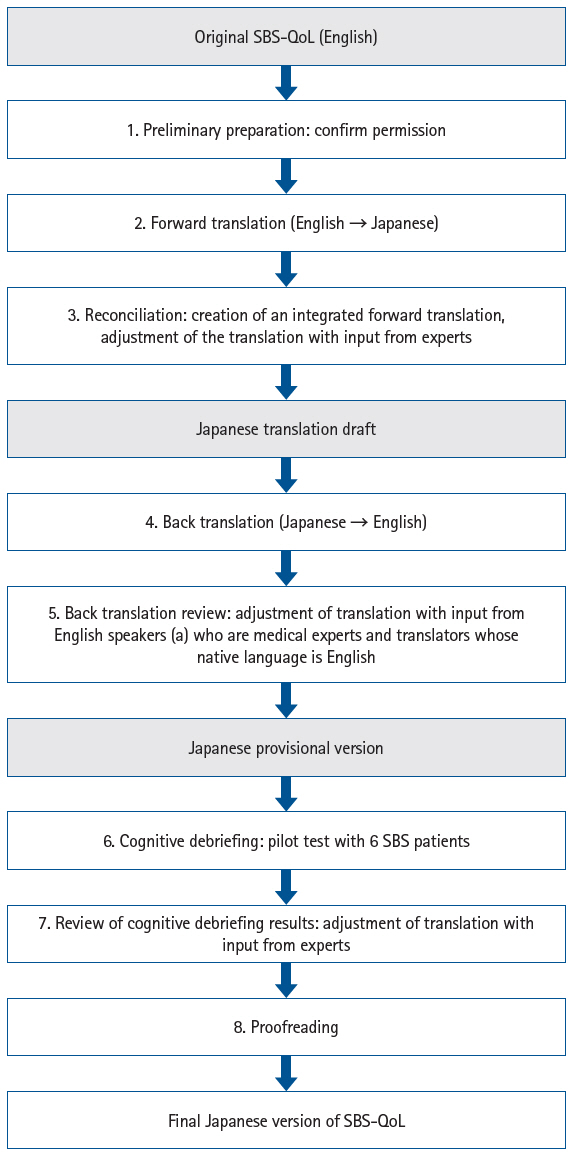

A provisional Japanese version was created in accordance with the guidelines of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Task Force, utilizing a process of forward translation, adjustment, and back translation.

-

Results

Cognitive debriefing using the provisional Japanese version was conducted with six Japanese patients with SBS. Based on these results, the Japanese wording was evaluated and revised, leading to the creation of the final Japanese version.

-

Conclusion

The Japanese SBS‐QoL, which has been confirmed to possess linguistic equivalence with the original English version, is expected to support the treatment of Japanese SBS patients, ultimately aiming to improve their QoL.

-

Keywords: Japan; Linguistic validation; Patient reported outcome measures; Quality of life; Short bowel syndrome

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Short bowel syndrome (SBS) is an intestinal malabsorption disorder characterized by a shortened small intestine, which results in insufficient absorption of nutrients such as water and electrolytes under standard nutritional management. This often leads to an inability to meet required nutritional needs. When intestinal adaptation fails to occur after small bowel resection, intestinal failure develops, making ongoing parenteral nutrition (PN) necessary [

1]. Patients with SBS present with a diverse range of clinical scenarios depending on the underlying disease, residual bowel length, the presence or absence of a stoma, and whether PN is being administered.

Studies have shown that patients with intestinal failure experience significantly lower quality of life (QoL) related to both physical and mental health compared to the general population [

2,

3]. For individuals requiring long-term PN, challenges include restrictions associated with home PN (HPN)—such as limitations in clothing selection and participation in leisure activities—as well as decreased physical strength [

4]. The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism’s guidelines for the management of adult chronic intestinal failure recommend regular QoL assessment as part of standard care [

5]. In Europe and the United States, multidisciplinary support for intestinal rehabilitation is well established, with the goals of improving prognosis, enhancing QoL, and facilitating social reintegration through optimization of PN tailored to each patient’s condition [

6]. For instance, reducing PN has been associated with improved QoL [

7]; however, excessive reduction can lead to dehydration and fatigue. Therefore, assessing both physical and mental burdens through QoL measurement is important for appropriate PN adjustment. In Japan, the importance of intestinal rehabilitation focused on improving patient QoL is also being recognized, and multidisciplinary teams are expected to evaluate QoL using standardized, reliable assessment tools. Additionally, the approval of teduglutide [

8] in June 2021 has expanded therapeutic options, further diversifying the content of intestinal rehabilitation, and the use of a standardized QoL assessment tool in treatment selection is considered highly valuable.

Prior to the development of the original English version of the Short Bowel Syndrome-Quality of Life (SBS-QoL), the QoL of SBS patients was assessed using comprehensive scales such as the 36-item Short Form (SF-36) [

2]. Although the HPN-QOL was developed to evaluate the QoL of patients receiving HPN [

9], it is not specific to SBS. The SBS-QoL is a patient-reported outcome (PRO) measure designed specifically for adult SBS, allowing for the measurement of changes in QoL over time, with patients assessing their daily life over the previous week using a visual analog scale (VAS) [

10]. Developed in 2013 during the international development of teduglutide by NPS Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Takeda GmbH [

10], the SBS-QoL has been used for QoL assessment in international clinical trials. The constructed scale consists of 17 items (

Table 1) [

10], created in accordance with classical test theory [

11] and the US Food and Drug Administration’s guidance on PROs [

12]. The SBS-QoL showed a moderately high correlation (r≥0.7) with the HPN-QOL and demonstrated strong construct validity. High internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.94), reproducibility (r≥0.95), and responsiveness (responsiveness index=1.84) have also been established [

10]. Despite having been translated into more than 10 languages, a Japanese version of the SBS-QoL had not previously been developed.

In Japan, it is essential to understand the actual living conditions of SBS patients and to evaluate treatment effects on QoL by capturing patient-reported subjective outcomes. Therefore, to develop a Japanese version of the SBS-QoL (©2023 Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited), we translated the SBS-QoL into Japanese and verified its linguistic validity.

Methods

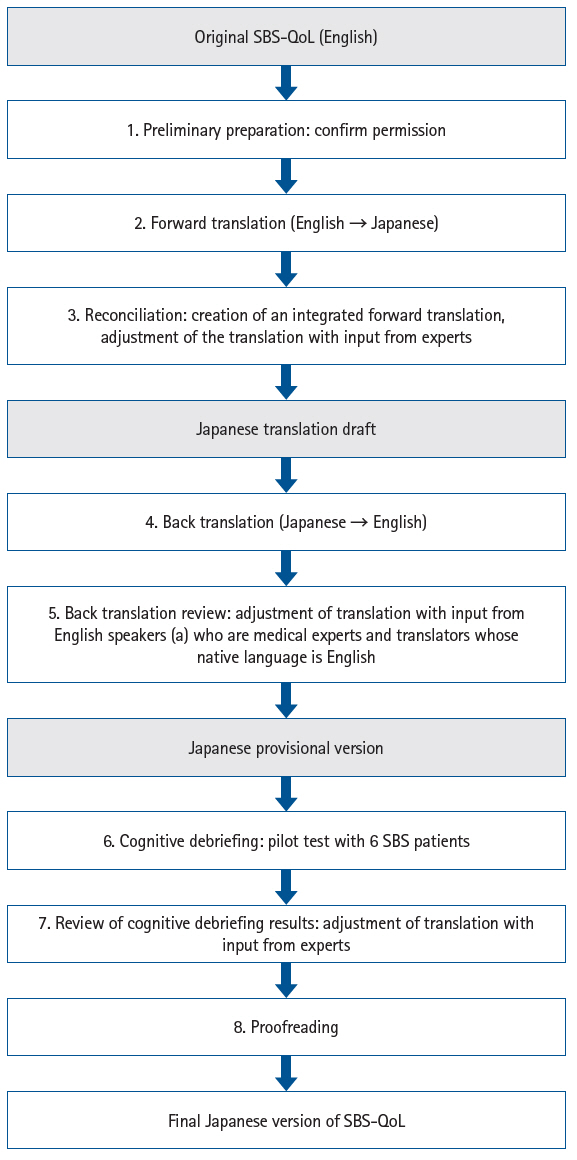

The development of the Japanese version followed the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Task Force guidelines, with reference to the User’s Guide for PROs and fundamental principles of scale translation (

Fig. 1) [

13-

15].

1. Preliminary preparation: Permission to translate the original SBS-QoL [

10] into Japanese was obtained from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, the copyright holder.

2. Forward translation: Two translators independently translated the original version into Japanese.

3. Reconciliation: The authors compared and integrated the two forward translations to create a Japanese translation draft that would be easily understood by Japanese SBS patients.

4. Back translation: Two translators, who were not involved in the forward translation, each translated the Japanese draft back into English.

5. Back translation review: One medical expert, who was a native English speaker, and one native English speaker, neither of whom was involved in the forward or back translation, checked the consistency between the two back-translated versions and the original. The authors revised any expressions suspected of inconsistency, resulting in a Japanese provisional version (hereafter referred to as the provisional version).

6. Cognitive debriefing: The comprehensibility of the provisional version was tested with Japanese SBS patients. Subjects were recruited from three medical institutions responding to a CMIC Healthcare Institute survey and were adult Japanese patients diagnosed with SBS. At recruitment, neither the underlying disease nor the presence of a stoma was specifically queried. Written consent was obtained, and one-on-one online interviews were conducted by a researcher experienced in PRO studies with six adult SBS patients between September 22 and October 25, 2022. All personal information was collected with strict attention to participant privacy. After explaining the purpose of the survey, participants completed the provisional version online, with the interviewer providing computer support as needed. Following completion, the interviewer reviewed the overall questionnaire for clarity, relevance to daily status, sufficiency of item number, and the clarity of each question, also confirming the rationale behind each response during the review of the VAS.

7. Review of cognitive debriefing results: The authors revised the provisional version’s wording based on feedback from cognitive debriefing.

8. Proofreading: The revised provisional version was proofread and finalized as the Japanese version of the SBS-QoL.

As this study did not involve translation into languages other than Japanese, the “Harmonization” step described in the ISPOR Task Force guidelines [

13] was not undertaken.

Results

Through the process of forward translation, reconciliation, back translation, and back translation review, a provisional version of the scale was created, followed by cognitive debriefing. Based on the findings from the cognitive debriefing, additional discussions were held regarding both the wording and the VAS, ultimately resulting in the final Japanese version of the SBS-QoL (

Table 1).

For item 3 (working life/ability to work), a sense of awkwardness in the wording was noted during the back translation review. As a result, the provisional version adopted the expression “仕事や作業” (“work or tasks”).

For item 8 (mobility and self-care activities), the initial forward translation used “移動や身の回りの管理” (“mobility and self-care management”), but to better reflect the original meaning and provide a more natural Japanese expression, the wording was changed to “移動や身の回りの動作” (“mobility and self-care activities”) in the provisional version.

For item 16 (skeleton/muscle symptoms), the forward translation was “骨格や筋肉の症状” (“skeletal and muscle symptoms”). However, after consultation with a medical expert during the back translation review, it was determined that including “joints” would make the item clearer and easier to understand. Therefore, the provisional version used “骨・関節・筋肉の症状” (“bone, joint, and muscle symptoms”).

Cognitive debriefing

The cognitive debriefing involved six participants: three men and three women. Two were in their 40s, one was in their 50s, and three were in their 60s. Among them, three were employed, four lived with family members, and they resided in three different regions of Japan. Five participants had Crohn’s disease as their underlying condition and also had a stoma. All participants responded to every one of the 17 items. Regarding the number of questions, five out of six participants (83%) felt that it was not excessive.

The time required to complete the provisional version—including support for navigating the online format—ranged from 5 minutes 40 seconds to 7 minutes 20 seconds (median: 6 minutes 7.5 seconds). All participants indicated that the questions were appropriate for assessing their daily lives; however, four participants reported difficulties in understanding certain points. Specifically, three mentioned that the VAS was difficult to understand, while two cited difficulty answering due to comorbidities (multiple responses were permitted). When asked about how daily life or health status had been affected by SBS in the past week, participants reported challenges in distinguishing whether symptoms were attributable to Crohn’s disease or SBS, or in one case, whether knee pain was related to SBS. Additional participant comments on specific questions are summarized in

Table 2.

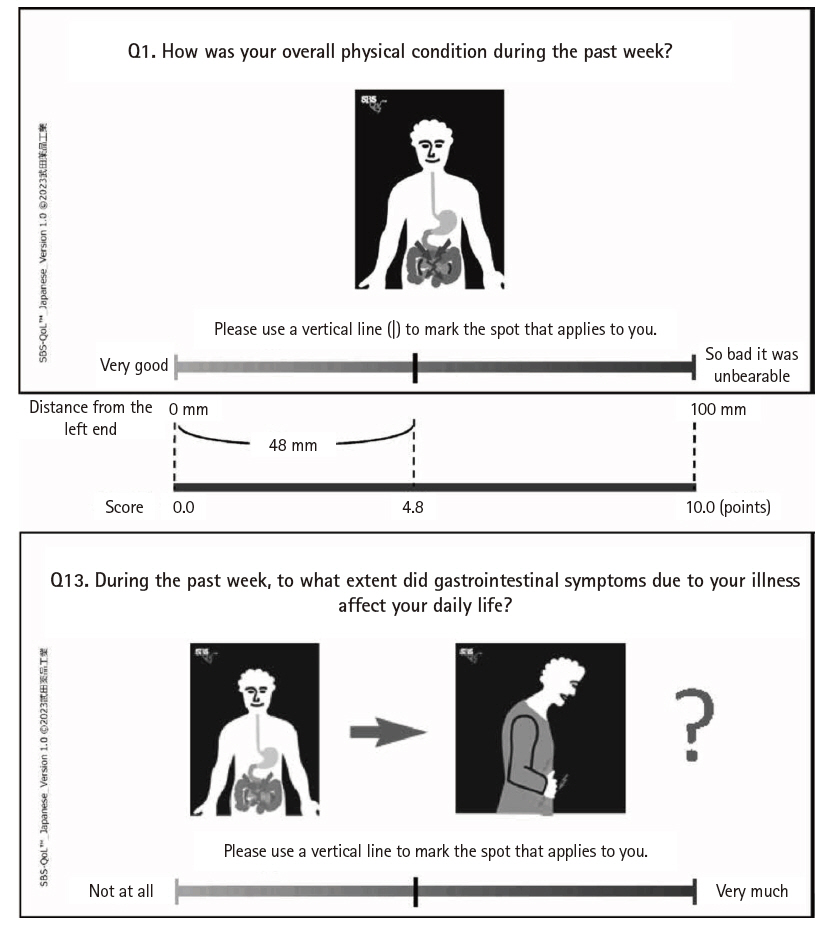

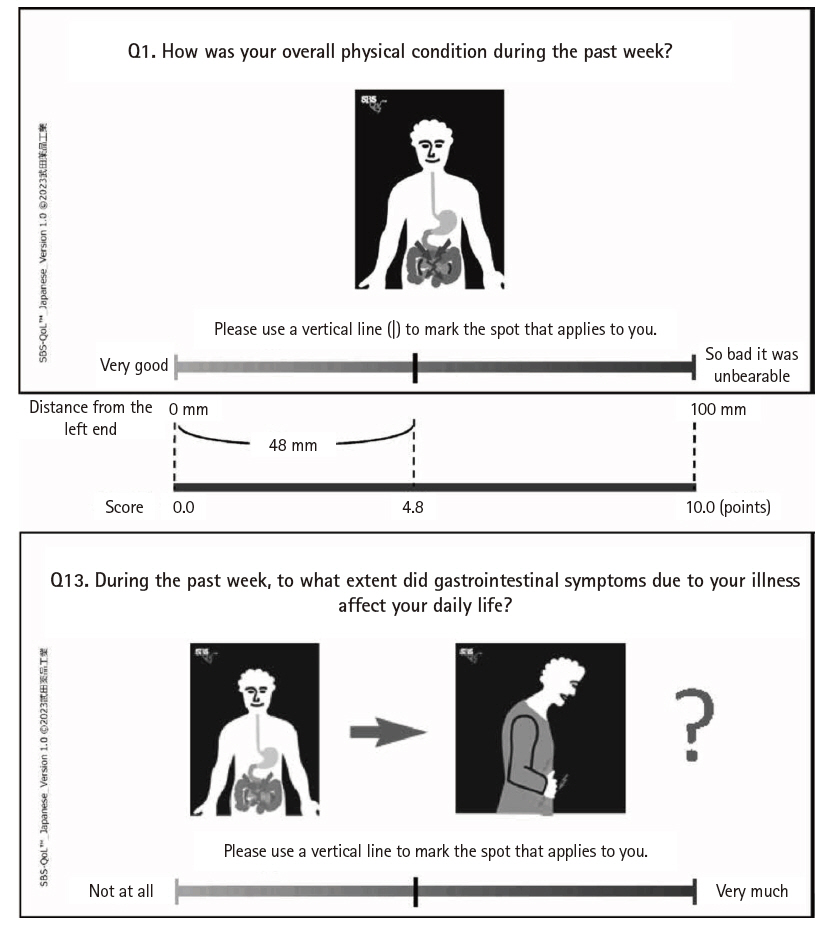

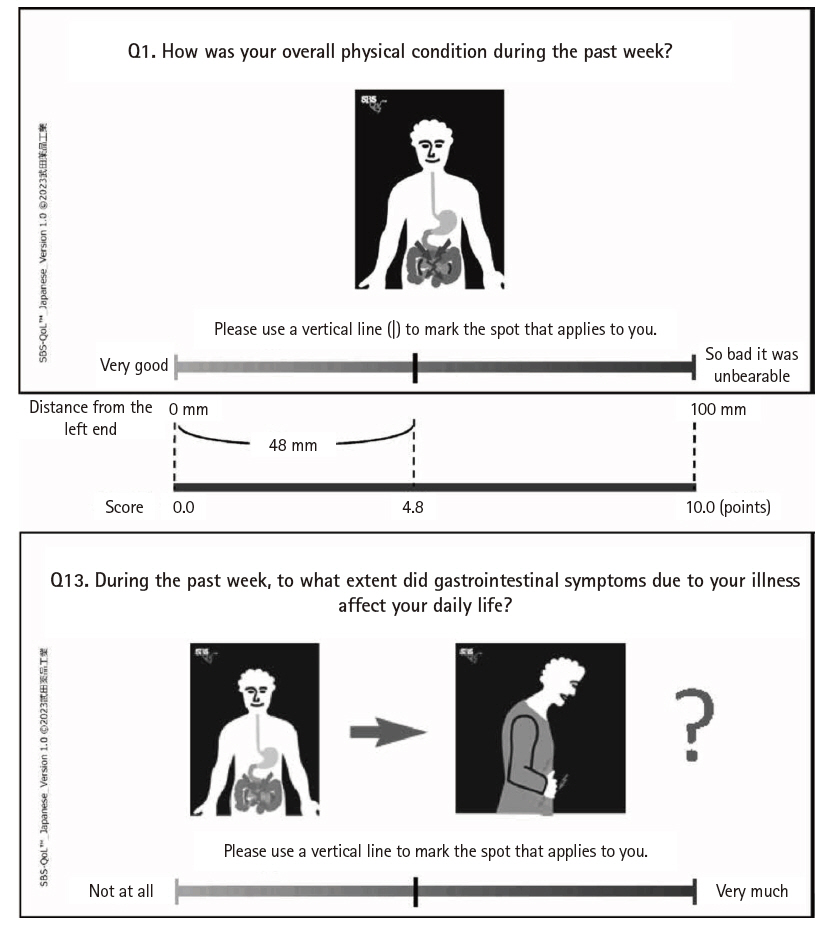

The response method for the VAS followed the original version: the distance from the left end of the line to the point marked by the respondent (0–100 mm) was measured, and the total score for all items (0.0–170.0) was calculated (

Fig. 2).

For item 1 of the VAS, the forward translation rendered “excellent” as “非常に良い” (“very good”). During the back translation review, it was noted that “非常に良い” is generally back-translated as “very good,” whereas “excellent” is a higher-level expression. There was concern that “非常に良い” might not fully capture the nuance of “excellent.” However, it was ultimately judged that for patients with chronic diseases, “非常に良い” (“very good”) was a more appropriate and relatable expression than “最高に良い” (“excellent”) when referring to the best possible condition.

During cognitive debriefing, participants provided a range of opinions regarding the VAS. Only one participant found it easy to use. Among those who experienced difficulty, comments included: “I would like tick marks on the VAS,” “It is hard to understand without a ‘normal’ indicator in the center,” “It would be easier if there were selectable options,” and “A 10-point scale would be easier to answer.” Despite these challenges, all participants were able to complete the questionnaire in its entirety.

Discussion

The SBS-QoL is a highly reliable, SBS-specific assessment tool that enables the measurement of temporal changes in the QoL of patients with SBS [

10]. In this study, we followed ISPOR guidelines to develop a Japanese version of the SBS-QoL that demonstrates linguistic validity equivalent to the original scale.

Utilizing the Japanese version of the SBS-QoL to assess QoL may allow clinicians to more accurately reflect changes in physical condition (including treatment effects and side effects) as experienced by patients undergoing intestinal rehabilitation. For instance, items addressing challenges in daily activities, work, or leisure may offer opportunities for healthcare professionals to identify mental distress in their patients. Additionally, during PN adjustment, items related to gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue, and eating habits can provide valuable information regarding physical changes as perceived by the patient. The degree of fulfillment in daily life can be efficiently assessed within the time constraints of routine clinical practice by focusing on items about sleep, social relationships, and activity level. These insights may help inform treatment goals for SBS patients. Furthermore, since small bowel transplantation was covered by insurance in Japan starting in April 2018, and there is increasing interest in the transition of QoL before and after transplantation, this scale may also serve as a valuable tool for longitudinal assessment of QoL in SBS patients undergoing transplantation.

The SBS-QoL employs a VAS method, in which respondents indicate their status on a line between two extremes (the left end representing the best condition, the right end the worst). Compared to selection-based methods such as “yes/no,” the VAS provides more detailed evaluation [

10] and is widely used in comprehensive assessments, such as for cancer-related pain. However, for elderly patients or those with cognitive impairment, the VAS can be complex, difficult to complete, and time-consuming. It cannot be used for telephone surveys, and aggregating results from paper forms can be costly [

16-

18]. In our study, some participants expressed a preference for numerical rating or Likert-type scales, which they found easier to use. Nevertheless, as shown in

Fig. 2, the VAS score of this scale ranges from 0.0 to 10.0 for each item, with a total possible score from 0.0 to 170.0. This scoring system is optimal for capturing subtle temporal changes in patient QoL [

10] and is considered highly suitable for QoL assessment in SBS patients.

Cognitive debriefing is conducted with individuals who are expected to use the scale, with the goal of confirming translation accuracy and the clarity of the questions. ISPOR Task Force guidelines recommend including five to eight native speakers of the target language as participants [

13]; in this study, six participants were included. If cognitive debriefing were conducted with patients with different backgrounds—such as those with other underlying diseases or without a stoma—responses might differ. However, in this study, responses were obtained from all participants, and five out of six (83%) stated that the number of questions was not excessive, indicating that the Japanese version of the SBS-QoL is sufficiently practical. It should be emphasized that the SBS-QoL was developed for adult SBS patients; thus, the Japanese version is also intended for adult SBS patients, and its suitability for pediatric patients or those with intestinal failure due to other causes remains unconfirmed.

In summary, we have created a Japanese version of the SBS-QoL that can be used in Japan, through careful linguistic validation from the original English version. The Japanese version of the SBS-QoL can be obtained by application and contracting through ePROVIDE (Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited; https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/). It is expected that this tool will help standardize QoL assessment for SBS patients in Japan and will be widely used to evaluate the effectiveness of intestinal rehabilitation, including the impact of new therapeutic agents. Furthermore, using the same assessment tool as in other countries may enable direct comparison of Japanese data with overseas results.

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: YT, MS, SK. Data curation: MS, SK. Methodology/formal analysis/validation: MS, SK, KI. Project administration: YT, MS, SK, KI. Writing–original draft: all authors. Writing–review & editing: all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

This study was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. Hiroomi Okuyama has received lecture fees from Takeda. Yuko Tazuke has no conflicts of interest to declare. Mayu Suzuki, Sae Kikuchi, and Kaori Ishiguro are employees and shareholders of Takeda. Except for that, no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This study was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited (hereafter, Takeda).

Data availability

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Social Information Service Co., Ltd., CMIC Healthcare Institute Co., Ltd., Mango Planning and Research Co., Ltd., and Ms. Yuriko Kikuchi and Ms. Hiroko Ebina of ProScribe Co., Ltd. (Envision Pharma Group).

Supplementary materials

None.

Fig. 1.Procedure for creating the Japanese version of the Short Bowel Syndrome-Quality of Life (SBS-QoL). A person whose native language is not English, but who uses English in daily life and is able to understand the original version. SBS, short bowel syndrome.

Fig. 2.Example of a response to the Japanese version of the Short Bowel Syndrome-Quality of Life (SBS-QoL) (item 1) and sample (item 13).

Table 1.Japanese translations corresponding to the 17 items of the original SBS-QoL

|

No. |

English version |

Japanese version |

|

1 |

General well-being |

全体的な体調 |

|

2 |

Everyday activities |

日常の活動 |

|

3 |

Working life/ability to work |

仕事や作業 |

|

4 |

Leisure activities |

余暇の活動 |

|

5 |

Social life |

人とのつきあい |

|

6 |

Energy level |

体力や気力 |

|

7 |

Physical health |

身体の健康 |

|

8 |

Mobility and self-care activities |

移動や身の回りの動作 |

|

9 |

Pain |

痛み |

|

10 |

Diet, eating and drinking habits |

飲食の内容や習慣 |

|

11 |

Emotional life |

日々の感情 |

|

12 |

Sleep |

睡眠 |

|

13 |

Gastrointestinal symptoms |

消化器症状 |

|

14 |

Fatigue/weakness |

疲労感や体力低下 |

|

15 |

Diarrhea/stomal output |

下痢やストーマの排液 |

|

16 |

Skeleton/muscle symptoms |

骨・関節・筋肉の症状 |

|

17 |

Other symptoms/discomfort |

その他の症状・不快感 |

Table 2.Participants’ opinions on the entire questionnaire and discussion results based on their feedback

|

Item No. |

Wording in the Japanese provisional version |

Participants’ opinions in cognitive debriefing |

Discussion results based on participants’ opinions |

|

3 |

仕事や作業 (“Work or tasks”) |

If asking about work, “tasks” is unnecessary. |

Although the interpretation of “tasks” varied among individuals, since participants could answer according to their own situations with the expression “work or tasks,” it was decided that no revision was necessary. |

|

Including “tasks” makes it seem like it includes physical labor or retail jobs. |

|

Participants who were not employed thought “tasks” referred to housework and could answer accordingly. |

|

6 |

活力(エネルギー) (“Vitality (energy)”) |

Difficult to understand; both “vitality” and “energy” feel awkward, other expressions would be better (3 participants). |

The original “energy level” seems to ask about a state where one lacks physical strength. However, since motivation may also decrease as physical strength declines, “活力(エネルギー)” was revised to “体力や気力” (“physical strength and motivation”). |

|

9,13-17 |

あなたご自身や日常生活 (“Yourself and daily life”) |

“Yourself” and “daily life” mean the same thing, and for items asking about the impact of symptoms, the symptoms are about oneself, so “yourself” is unnecessary (2 participants). |

The wording “yourself and daily life” in the provisional version was revised to “your daily life.” The same revision was made to the Japanese translation of items 13, 14, 15, 16, and 17, which included the same wording. |

|

10 |

食事や飲食等の食習慣 (“Diet, eating and drinking habits”) |

“Diet” and “eating and drinking” mean the same thing, so only one is needed (1 participant). |

“食事や飲食” (“diet or eating and drinking”) was revised to “飲食の内容や習慣” (“contents and habits of eating and drinking”). |

References

- 1. Tazuke Y, Ueno T, Kimura T, Bessho K, Okuyama H. Short bowel syndrome and nutritional management. Pediatr Surg 2022;54:289-95.Article

- 2. Bluthner E, Bednarsch J, Stockmann M, Karber M, Pevny S, Maasberg S, et al. Determinants of quality of life in patients with intestinal failure receiving long-term parenteral nutrition using the SF-36 questionnaire: a German single-center prospective observational study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2020;44:291-300. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 3. Kalaitzakis E, Carlsson E, Josefsson A, Bosaeus I. Quality of life in short-bowel syndrome: impact of fatigue and gastrointestinal symptoms. Scand J Gastroenterol 2008;43:1057-65. ArticlePubMed

- 4. Carlsson E, Berglund B, Nordgren S. Living with an ostomy and short bowel syndrome: practical aspects and impact on daily life. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2001;28:96-105. ArticlePubMed

- 5. Pironi L, Cuerda C, Jeppesen PB, Joly F, Jonkers C, Krznaric Z, et al. ESPEN guideline on chronic intestinal failure in adults: update 2023. Clin Nutr 2023;42:1940-2021. ArticlePubMed

- 6. Hiroomi O. Intestinal rehabilitation: a review. Surg Metab Nutri 2020;54:217-20.Article

- 7. Jeppesen PB, Pertkiewicz M, Forbes A, Pironi L, Gabe SM, Joly F, et al. Quality of life in patients with short bowel syndrome treated with the new glucagon-like peptide-2 analogue teduglutide: analyses from a randomised, placebo-controlled study. Clin Nutr 2013;32:713-21. ArticlePubMed

- 8. Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. Interview Form: Revestive® Subcutaneous Injection 3.8 mg/0.95 mg [Internet]. Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited; 2023 [cited 2023 Sep 13]. Available from: https://www.takedamed.com/medicine/detail?medicine_id=565.

- 9. Baxter JP, Fayers PM, McKinlay AW. The development and translation of a treatment-specific quality of life questionnaire for adult patients on home parenteral nutrition. E Spen Eur E J Clin Nutr Metab 2008;3:e22-8. Article

- 10. Berghofer P, Fragkos KC, Baxter JP, Forbes A, Joly F, Heinze H, et al. Development and validation of the disease-specific Short Bowel Syndrome-Quality of Life (SBS-QoL™) scale. Clin Nutr 2013;32:789-96. ArticlePubMed

- 11. Novick MR. The axioms and principal results of classical test theory. J Math Psychol 1966;3:1-18. Article

- 12. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. FDA; 2009.

- 13. Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, et al. Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health 2005;8:94-104. ArticlePubMed

- 14. Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (JPMA); Data Science Subcommittee Task Force 7. Patient reported outcomes in clinical trials: a guide to using PROs for clinical developers. JPMA; 2016.

- 15. Inada N. Improving the methodological quality of the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcome measures. Jpn Assoc Behav Cogn Ther 2015;41:117-25.

- 16. Paice JA, Cohen FL. Validity of a verbally administered numeric rating scale to measure cancer pain intensity. Cancer Nurs 1997;20:88-93. ArticlePubMed

- 17. Couper MP, Tourangeau R, Conrad FG, Singer E. Evaluating the effectiveness of visual analog scales: a web experiment. Soc Sci Comput Rev 2006;24:227-45.

- 18. Yamada K, Erikawa S. Evaluating the effectiveness of visual analogue scales in a web survey. Toyo Univ Fac Sociol Bull 2014;52:57-70.

, Mayu Suzuki2

, Mayu Suzuki2 , Sae Kikuchi2

, Sae Kikuchi2 , Kaori Ishiguro2

, Kaori Ishiguro2 , Hiroomi Okuyama1

, Hiroomi Okuyama1

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN

Cite

Cite